|

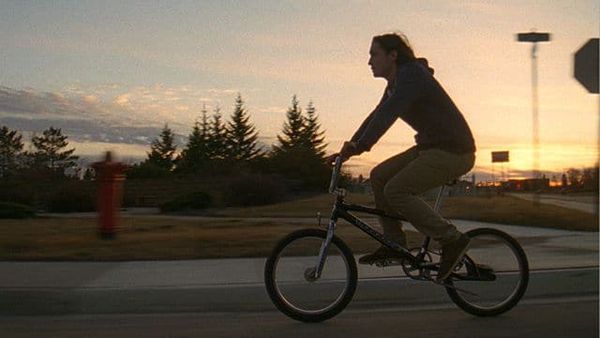

| Max Records in I Am Not A Serial Killer |

Director Billy O’Brien’s adaptation of Dan Wells’ teen fiction novel, I Am Not A Serial Killer tells the story of John Wayne Cleaver (Max Records), a teenager diagnosed with sociopathic tendencies who finds his small Midwestern town stalked by a killer. The film played as part of the Cult strand at this year’s BFI London Film Festival, where O’Brien looked back on the making of the film with Eye For Film, offering insights on film production and exhibition.

In the second of a two part I Am Not A Serial Killer interview series, O’Brien reflects on the luck and unpredictability that lends low budget filmmaking its wild nature. He also briefly shared his thoughts on silence versus dialogue across film and television, while discussing his approach to comedy, the inevitability of hindsight and the question of whether or not film can be a transformative experience.

|

| Bullies pick the wrong target |

Paul Risker: In the four year gap following the test film, you expressed your concerns that Max, who was then at the right age to capture youth and the coming of age, could have outgrown and even lost interest in the character. Would you describe the film as a fortuitous experience?

Billy O’Brien: Completely! It was a nightmare to get to the start line in terms of the fruitless years of trying to raise the finance. But then one of the things that I do believe is there's a sort of unpredictability and wildness in a small independent film that you wouldn't have in an animation, or in one of those big pre-visualised films. We were downright lucky that it worked out with Max. If we had done it when he was younger it would have been a different performance, and a tougher one for him with the stamina required to be in every scene. There were a number of things that could have affected that, so we'll of course never know, but I think it was the right time when we did do it. So we just lucked out and that's what I like on smaller ones, where on set you have your plan of how you are hoping to shoot it, but you keep an eye open for anything magical that can happen. There are all of these different things and I try to make use of them. It drives me nuts at times, but I think it just brings something to the screen.

PR: It is difficult to imagine the film working without the strength of either Max or Christopher’s performance. I always appreciate the silent side of an actor's performance, and both Max and Chris bring a silent physicality that beautifully embodies their characters.

BO'B: Absolutely! Dan Wells said something very complimentary. In the book the whole story is told through first person. You're in John's mind, you're in his thoughts, and Dan said, "In the film they didn't do that, but what they had instead was Max Records’ face", and I think that's so true. We wouldn't be talking about the film now if that role had failed, whether it be bad casting or whatever, because nothing that I could have done could have saved it. Other holes you can save in the editing where you can hope that you get by, but a film like this, it's all on his shoulders. I thank the lucky stars on that. But no, both of them. Chris is known for his physicality and even though he's a lot subtler here, he still brought a silent film character to it. So even when he's in the distance you can see it in his body language, and I love that.

|

| Who's watching who? |

PR: Silent cinema is spoken of in the past tense, seen to have ended following the emergence of sound cinema. In reality silent cinema has endured through the work of writers, directors and actors that understand silence as a tool.

BO'B: Look at the opening sequence in No Country For Old Men when Josh Brolin's out hunting the deer, and he comes across the whole clusterfuck in the desert. There's not a word spoken in like 20 minutes and it is the most extraordinary bit of cinema. It's just beautiful and interesting, and you are riveted, but it's not somebody telling you stuff. It's why I haven't done TV really. I did a Sci-Fi Channel movie, but it was a 35mm movie. The idea of a room and two people just talking endlessly... Look, don't get me wrong, Social Network is an extraordinary film, and that quick fire dialogue is astonishing. But there is a lot of bland TV where it's just literally, plonk, plonk, two people talking and deadly boring. I went to art college and I love the visual. I loved the idea of how the body sitting in the chair when you walk in could tell you so much.

PR: One of the challenges when dealing with comedy is that if not balanced it can stifle rather than complement the film, specifically the horror elements.

BO'B: It wasn't conscious that we said we've got to make this funny. It came from the book. When I wrote a letter to Dan Wells looking for the rights, I said the dark strand of humour is almost like Russian literature. I'm not an expert on Russian literature, but it had that other kind of Finnish humour – that wonderful strand coupled with the fact of the snow. This was important to me because my first film, Isolation, was a grim horror. It was important to me to make the film that way, but I have never done anything before or since that has been so grim, and I really do like the humour in this. All I was trying to keep an eye on here was that in the physicality of the shoot we didn't lose this delicate strand of humour.

|

| John doesn't like Halloween |

It's controversial because a lot of financiers didn't quite understand what to do with it, and when we premiered it at South by Southwest it took me a few readings of reviews from a couple of famous horror sites to realise, oh shit, they don't get the humour at all. They actually thought the humour meant there was a mistake somewhere because to them it is a horror film, and probably, going off my old films, they were thinking it should be. But instinctively for me it felt right all the way through the shoot and then the editing. I had a wonderful editor in Nick [Emerson] who did Starred Up and has just done Lady Macbeth. We discussed it a lot, and if we laughed we felt it was good. And I can still remember showing Rory Gilmartin from the Irish Film Board the rough cut in our edit room. It was the first test of an outsider coming in and it is always a crucial bit. You don't sleep the night before. When I heard him chuckling at the right parts (God knows if he chuckled at the wrong bits), and he turned and his eyes were sparkling, and he just said,"Well that's quite a trick", I thought, great, that's a good reaction.

PR: Thinking about your use of the word instinctive, could the humour be contextualised as a naturally forming soundtrack within the film?

BO'B: There's stuff that came up on the shoot and last night the funeral scene got a big laugh when John’s handing out the brochures and Brooke hugs him, and people continue to take one. Well I can't take credit for that. What happened there is you have extras that are told to take a brochure from Max Records and to go and sit, and even though he's hugging the girl they are not going to stop taking them. So they kept doing it and when we looked through the rushes everyone was chuckling. And Lucy, who played Brooke, had never acted before. She was quite nervous, but I think she's wonderful in the film. It's only a little role, but there's a scene in the film where she comes across John in the library with his headphones on. He doesn't hear her when she calls his name and so she shouts it. We did about five takes of that, but she was too nervous to shout and so I took her to one side and said,“Listen, Max is slightly method in that's he quite intense. The point is he's not going to see you unless he feels like you've really cut through the music. You are going to have to shout it." So she did this great thing where she shouted it and was embarrassed with herself. It is a really sweet and funny moment. So again I wouldn't take credit for that in the sense I couldn't predict that she'd do that. But it's lovely, and that's again the unpredictability that it brings when you've got the right group of things together. So I would say that maybe because we already had that strand there, we were looking out for those things, and if I had been setting out to make a serious grim thing, then I would have used a different take.

|

| I Am Not A Serial Killer poster |

PR: Speaking with Carol Morley for The Falling, she explained: “You take it 90% of the way, and it is the audience that finishes it. So the audience by bringing themselves: their experiences, opinions and everything else to a film is what completes it.” Would you agree and do you perceive there to be a transfer of ownership?

BO'B: Absolutely, and I have let this one go. I am very relaxed about it now. Robbie Ryan the cameraman, he just saw it for the first time with all the bells and whistles on. He'd seen the rough cut, but not in the cinema. He was doing a Noah Baumbach film in New York when we were in South by Southwest. I think Robbie liked the film [laughs], but he pointed out about five problems with it. This is what he does, it's his job. I would agree with some of them, but I didn't know about those problems back when we were making the film, and in retrospect you could look at points and say, “Yeah that's true.” And even the title, it’s quite clear from Twitter comments that it's a Marmite name. There are an awful lot of people saying on Twitter, "What a surprise...Really enjoyed this, but not what I expected." So there's a b-movie, serial killer, grim horror resonance because we used the word serial killer in the title. In retrospect we maybe should have abandoned the name of the book and called it something that would have allowed them in more. I don't know, and it's something we didn't predict because we were basing it on a book, so we never even thought of changing the name.

PR: And in retrospect do you perceive there to be a transformative aspect to the filmmaking process, wherein you are a different person to the one you were before the film?

BO'B: I saw Robert Altman being interviewed about that. Something was said about how you basically do a good film and a bad film, and Robert Altman in the very gentle way he spoke said, “Well I don't see it like that. I see that I made the same film and the audience drifts away, and comes back.” So I don't know, I haven't analysed it about being the same person. I know that shockingly if Nick Ryan knew in 2009 or 2010 when I approached him about doing this that it would take this long and there would have been this much heartache of trying to raise the money, we would probably not have done it. It has just been really tough and long, but on the other side we are all really happy with it. If it had been a disaster then it would have been the worst of both worlds – six years making something that nobody wants to see [laughs]. But no, we are really happy with the film, but whether we'll do that again is another thing.

For me, I learn each time. I love looking at studio pictures in terms of the directors and one of the things I deeply regret is that John Ford, when he was 30, had made a hundred films. Now the bulk of them were shorts, but these were shorts that were 40 minutes long, and the experience a director gets from that. I get to make a film if I'm lucky every two or three years. It's like air hours for pilots and if I add up all my hours for a career that's only 20 years long, it's not that much. So my New Year’s resolution is to try and get more films out because you just learn so much.

Read part one of our interview with Billy O'Brien here.