|

| Stephen Kijak: 'We just went full on... starting from a place of intimacy' Photo: Manga Entertainment/Passion Pictures |

In conversation with Eye For Film, Kijak reflected his filmmaking journey while offering his thoughts on the relationship between narrative and documentary filmmaking. He also discussed the unintentional nature of the filmmaking process and how We Are X benefited from the approach of discovery, as opposed to familiarity.

|

| Director Stephen Kijak: 'Music films to me are like these cinematic mixed tapes. I want them to flow, to feel like the music and to turn people on' Photo: David Arenas |

It's a little bit of both. Honestly, I came up through film school and really focused on screenwriting - I was never at all focused on documentary. I studied under the great Cassavetes expert Ray Carney at Boston University, and I tripped out on Lynch, Godard and Antonioni very early on. It was really a Euro-centric sort of film interest, and a lot of film noir. I was primarily a writer and so the first film, Never Met Picasso, which I'm proud of in a way, was a bit of a misfire - a youthful sort of experiment that didn't quite take off. I ended up stumbling into documentary and it saved my ass [laughs] – it really did. It gave me a real path and direction, and when it came to doing the third film Scott Walker, which was a passion project for me, it just brought all my interests into focus.

I love music, I played music, I worked in record stores - it was just a driving force in my life and that one crystallised everything. From there on, they've just come to me. There's a moment when you need to push and fight for your creative life, and there are moments where a more zen path of least resistance approach works best. It has served me well, from The Rolling Stones to The Backstreet Boys, and now X Japan. It has been an interesting journey and then you're right because the next thing that was very conscious was: let me build a bridge back to narrative through music. This was partly by necessity and, I think, the world at large seeing you has something else - I'm a music guy now for better or worse. But again, I grew up being obsessed with The Smiths and what better way to step back into the narrative world than through another personal passion. So yeah, it's that combination of circumstance and dedication I suppose.

There was a time when narrative features and documentaries were discussed independently of one another. It appears this divide has now been bridged, allowing both to be discussed as storytelling forms. With your initial interest in narrative fiction, how has this influenced your approach to documentary? Do you approach it as a form of storytelling?

I try not to make distinctions. I think the main distinction for me is methodology, and I'm not sitting there scripting my documentaries. It's just more about the process of how you're generating the material - a story is factual or it's not. A lot of the dramatic and narrative urges behind them are the same. My co-director Angela Christlieb on Cinemania, my first documentary experience, has gone on to make some really whacked out, brilliant, experimental documentaries. She'd been an art filmmaker, studied at The New School doing experimental shorts, and neither of us really had a foundation in it. She brought a unique visual language and I had been studying screenwriting. So I had more of a grasp of form and was able to bring that to bear on how we shaped the story because ultimately it's just storytelling. You have to work dramatically with the elements you are given and again the approach is always cinematic.

|

| Stephen Kijak: 'It's all about a tone and a vibe, balancing elements in a way that gives you that when you know you've landed' Photo: Manga Entertainment/Passion Pictures |

Music films to me are like these cinematic mixed tapes. I want them to flow, to feel like the music and to turn people on. So the guidelines you might apply to a documentary are slightly different. I don't know if I've sort of evolved a certain way of doing things that has a lot to do with feel and rhythm. I used to play the drums and when I'm working with an editor who might not have as much of a kink for music as I do, I run into problems. And now I'm really curious to see how after all this time I can apply that back to narrative. It is slightly daunting, but also very exciting to think about switching back and exploring a more controlled version of that.

When I speak to documentarians they often cite the laborious task of sifting through the mass of raw footage. For some there is the knowledge of what the film will be, while for others it is a process of discovery. How do you compare and contrast the film you had in your mind versus the final version of the film?

Each one is really different and things start to come into focus in the edit, but this was a really hard edit, with two different editors. I don't want to go into it too much, but it was a process of an extended amount of time of just not being able to see it. I just could not pull it into focus – something wasn't right. It was an arduous experience and I knew that I had it in my reach when I saw the archive. Looking back at what we filmed at Madison Square Garden was so bizarre and visually stimulating that I was thinking, “Where is the story? What's not clicking?” There's a point when a scene or one little moment has the seed for everything and you say, “Okay, if the whole thing can feel like that we're good.” And, weirdly, we had the very beginning and the very end sketched out in a way that I felt, “Ah, it can start here and I know it can land here; what the fuck goes in the middle?” [Laughs] It was really difficult and we ended up 32 weeks in with a bit of a mess of a movie that needed a new direction. It was one of these that we found at the 11th hour - somehow we just took a radical approach for recutting and reconceiving it, and it just appeared. It's hard to describe the process because it's different for each movie. There are a lot of intangibles and it's less about what you envision and, going back to what I said earlier, it's about feel. It's all about a tone and a vibe, balancing elements in a way that gives you that when you know you've landed. It's just a gut thing I guess, but it was a tricky one.

Compared to your other projects where you first knew the bands from the outside looking in, how has this experience differed? How has your perception of Japan X evolved through the privileged opportunity to discover them in close proximity?

We just went full on and I got a team that wouldn't give a fuck - would blow through managers and just go into dressing rooms, start from a place of intimacy and assume we are one of you, and we are along for the ride. And Yoshiki was very aware that he had to open all the doors if it was going to work. An interesting antidote early on during the whole Madison Square Garden experience was the production manager of the tour was a real jerk [laughs]. We were like this big pain in his ass and the resistance was piling up until we complained about it a bit. Word came down that Yoshiki had said the only reason he was doing this was: “So I can have a film about doing this. You put them at the top of the priority list and just get the fuck out of their way. This is for them.” And that was a revelation. I was like, “Oh my God”, because they were really prioritising this, and you do sometimes feel like you are the mosquito buzzing around that they are always trying to swat away. This was the total opposite and so it was a unique position to be in with a band this big.

|

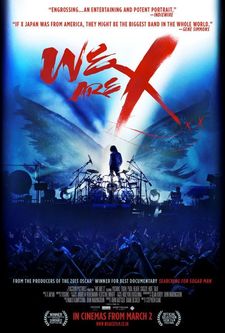

| We Are X - poster |