_600.jpg) |

| Gay Talese on James Baldwin: "Baldwin had his words and his voice in the forefront of the change in American politics." |

In the 1960s, Gay Talese developed a friendship with James Baldwin when they were regular contributors to Esquire magazine along with Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Gore Vidal, William F Buckley Jr, and others and he stayed in touch with Baldwin until his death in 1987. In Raoul Peck's I Am Not Your Negro, James Baldwin's writing is voiced by Samuel L Jackson over clips from movies that include an Indian-shooting John Wayne in John Ford's Stagecoach, Harry Beaumont's Dance, Fools, Dance with a tap dancing Joan Crawford, Sydney Poitier and Rod Steiger's goodbye in Norman Jewison's In The Heat Of The Night, and Richard Widmark's breakdown in Joseph L Mankiewicz's No Way Out.

|

| Anne-Katrin Titze captures High Notes author Gay Talese Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

Gay Talese notes that one of the New Yorker's great achievements was when editor William Shawn published James Baldwin's Letter From A Region In My Mind. Truman Capote's In Cold Blood and Rachel Carson's The Silent Spring also appeared in the magazine in the Sixties.

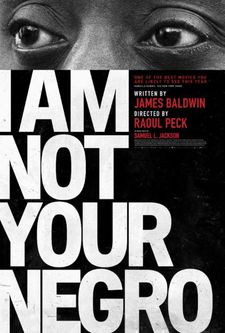

After winning the Panorama Best Documentary Award at the Berlin International Film Festival last week, the Oscar nominated I Am Not Your Negro will screen in the Glasgow Film Festival this week and is the opening night selection for the Human Rights Watch Film Festival in London next month.

Anne-Katrin Titze: The relative obscurity of James Baldwin now may change.

Gay Talese: Baldwin was a major gentleman of letters. He was not a commercial writer or a writer of topicality or a writer of current interest. His interest was historical and I think it was as much of the history of the 1920s, of the period of Richard Wright or Paul Robeson. Or earlier of Booker T Washington. This man, Baldwin, was, I thought, a writer of the age of black people of the time pre-Civil War, the period of slavery to where we are.

AKT: I loved that the film uses Baldwin's words. Here is a quote from the film: "History is not the past, it is the present. And we carry our history with us. We are our history. If we pretend otherwise, we literally are criminals."

GT: If nothing else, this documentary will introduce 24-year-old people, no doubt for the first time, to the name James Baldwin. And maybe pique their curiosity to the point of buying a book. On the internet. By Baldwin. And then they're going to be introduced to one of the magical writers. Fiction as well as nonfiction writers. I'm a post World War II person and now at 85 have a sense that people of 25 are on another planet from where I am because of the technology.

_225.jpg) |

| Gay Talese: "If nothing else, this documentary will introduce 24-year-old people, no doubt for the first time, to the name James Baldwin." |

There is another world, almost a silent planet within the world we know that isn't connected to the world we know. It's not on the map. And these people who are not on the map sometimes do remarkable things. They do for example elect a president that we never thought was going to be president. But we never thought that the people that put this president in power - we didn't know they were there. Everybody is talking about a silent majority. It's not that they're silent, they were unidentified. It's not that they were like a sleeping dog and it doesn't wake up - these are people we didn't even know were part of the population.

And we certainly didn't imagine they had feelings because we were so engrossed in our own sense of righteousness and justification for our actions as a political force or a human force that we didn't know we were doing anything by way of ignoring great numbers of other people. I guess, unless there is a riot there is no way to know about unhappiness that's outside our boundaries of awareness. And that was probably true moreover during Baldwin's time. More than it is now.

Because until the riots - perhaps Watts in 1965 or the riots in Harlem in '64 before the marches '65 that led to the Voting Rights Act, all those confrontations and lunch counters at the time of the Freedom Riders - but unless we have sit-ins and stand-ins and riots and fire - The Fire Next Time is Baldwin's phrase - we don't really know about these. And we don't really think about poor white people. We call them White Trash and sometimes they are featured in movies, such as that sheriff played so well against Sydney Poitier in the movie.

|

| Sydney Poitier as Virgil Tibbs and Rod Steiger as Police Chief Bill Gillespie - In The Heat Of The Night |

AKT: In The Heat Of The Night.

GT: Yes. What's the name of the actor?

AKT: Rod Steiger.

GT: Rod Steiger! One of the great performances in film, evoking the spirit of a redneck. And here is this Jewish guy from Poland [Steiger as Sol Nazerman in Sidney Lumet's The Pawnbroker (1964)]. I don't know where Rod Steiger's from. It's amazing, the acting talent he had to transfer his background. He could be the pawnbroker in one film and a sheriff in another.

AKT: Perfect clip of them used by Raoul Peck in the documentary.

GT: That's what I'm saying.

AKT: Also the clip with Richard Widmark [in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's No Way Out].

GT: That's right!

AKT: On the other hand, I was slightly puzzled by the choices to illustrate "grotesque white innocence," as symbolised by Gary Cooper and Doris Day.

GT: That's right. Of course, John Wayne and then how "the Indians were us." Baldwin is saying "we're the Indians" while he's cheering John Wayne. That's wonderful stuff.

|

| Lincoln Memorial 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom |

AKT: The juxtaposition of what Baldwin was saying and the film clips is very powerful.

GT: What's so amazing is that William Shawn, this gnomish little silent editor of the New Yorker, would have the courage - I think it was he - to publish Baldwin's essay. The Fire Next Time - it had various titles. What he wrote in the New Yorker was called something else. Something From The Region Of My Mind.

AKT: It was called Letter From A Region In My Mind (1962).

GT: This introduction in the pages of the New Yorker was one of the great publishing achievements of the New Yorker. Truman Capote's In Cold Blood (1965) was there. So was, I think, The Silent Spring (1962) writer [Rachel Carson], that led to the whole ecology movement. But lets not get off subject. So Baldwin, we hope, is in revival. At least that movie was achieved and I don't believe that that's the end of it.

AKT: I agree. Well, it's nominated for the Academy Award as one of five documentaries. A point Baldwin makes that also made me think of you is what he calls the failure of private life. It's a big part of the movie, too, where he is ranting about Americans having their heads filled with all this garbage. There is the public persona and then there is the "failure of American private life." Isn't that what you have been writing about as well over the years?

GT: I'm honored to be … But he was very determined, very stubborn. He was broke, he didn't have a lot of money, I don't know if he had any money at all. But I remember that one experience when he wouldn't write that piece that would go with the art. In those days when you had to release an artist's work - the artist Tommy Keogh’s color illustrations - that would go ahead of the editorial. The magazine would send the art ahead first and then the words could come later.

|

| In High Notes, Gay Talese writes about a recording session with Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: That's how you got to go to Harlem and write an essay called Harlem At Night instead of James Baldwin?

GT: That's right. He wouldn't do it. I don't know what he wrote but whatever he wrote was not published. And he wasn't going to do another version. So I did that. I felt so embarrassed. I don't think I did a good job because I didn't have time, it had to be done over a weekend and I didn't bring much to it except reporting. It wasn't from a region in my mind because I had no region that could connect with the reality of Harlem.

My trips to Harlem were more as a reporter covering a riot. I have covered two of them there before this incident I'm talking about. I was a reporter in Alabama. I covered the Selma March in '65. But what was I? I was a voyeur. That's all I was. And remained in a way. Baldwin, little preacher's boy from Harlem, escaped his country and went to France. And I never quite had him explain why he had to come back.

AKT: Because he felt he had to fight.

GT: Maybe because of the beginning of what we would know as the Civil Rights Movement. Simmerings of it.

AKT: That he had to and couldn't just sit back and watch from Paris.

GT: What's so amazing from this film - how the ministers and other activists recognised him so quickly as their chronicler, their literary voice. He really was immediately propelled into the limelight with them. Harry Belafonte, or other people were stars. They were celebrities. The ministers became celebrities in a sense because of their prevalence in the news and their pictures in the newspapers and magazines and television. But he [Baldwin] was a scrivener, a man of solitude, a writer. Baldwin had his words and his voice in the forefront of the change in American politics. But, I mean, this street does not to this day have a black neighbor. Where are we in the second decade of the 21st century? That's why this film is so important.

|

| John Wayne as Ringo Kid in John Ford's Stagecoach |

AKT: It is so relevant. A last quote from him: "My responsibility as a witness was to move as largely and as freely as possible to write the story and to get it out."

GT: Did you as a woman of high intellect ten years ago know about James Baldwin?

AKT: Yes. But not very much. The film was absolutely eye-opening.

GT: Isn't it amazing they got the money for that?

AKT: Yes and the idea of the structure - to take these thirty pages of notes [for Remember This House] about his three friends [Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr] who all were assassinated.

GT: I didn't realise until seeing this documentary that Joan Crawford was a dancer, for Christ's sake, in silent films. Did you know that? You knew that?

AKT: Yes, she was in the first movie Fred Astaire ever did. Dancing Lady.

GT: Silent movie?

AKT: No, that was in the early Thirties.

|

| I Am Not Your Negro poster |

GT: So she could dance that well? Amazing!

AKT: That clip was great. I loved that clip. And she always has prominent elbows in her dance moves.

GT: You said haven't seen Feud [Jessica Lange as Joan Crawford and Susan Sarandon as Bette Davis] yet?

AKT: I haven't.

GT: I think you'd be interested in it. I want to see the original film, Whatever Happened To Baby Jane?. You saw it?

AKT: Yes, I've seen it.

GT: Is it a great film?

AKT: No. Absolutely not. The film is this grotesque thing. I don't like it when actresses at a certain age are cast in horror movies. It was a trend - after you're 60 or something like that, all you get to do is horror movies. Is it so horrible to be a woman of that age? I don't know. I always detested that.

GT: You don't have to worry. You're so good-looking.

AKT: Let's take some photos.

Read what Gay Talese had to say on a dinner party with James Baldwin and Tom Wicker, Bureau Chief of the Washington Bureau of The New York Times.

Public screening at the Glasgow Film Festival: Wednesday, February 22 at 6:00pm - Glasgow Film Theatre.

The Glasgow Film Festival runs through February 26.

I Am Not Your Negro will open the London Human Rights Watch Film Festival on March 6.

The London Human Rights Watch Film Festival runs from March 6 through March 17.

I Am Not Your Negro is in cinemas in the US.