|

| Sunset (Napszállta) director László Nemes between Martin Scorsese and Frederick Wiseman: "In my childhood I was incredibly affected by tales, a lot of tales." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

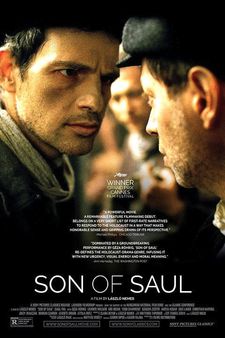

In the second half of my conversation on Sunset (Napszállta) with the director of the Oscar-winning Son Of Saul (Saul Fia), László Nemes spoke about the influence of fairy tales, FW Murnau's Sunrise, "creating imagery that is in the mind", and the "mission of cinema." He mentioned Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow Up as a film that "would not give you exactly the answers" and I thought of Charles Laughton's Night of the Hunter and John Huston's African Queen for his boat scenes in Sunset.

|

| László Nemes on Írisz (Juli Jakab): "I'm interested in transmitting something and sharing something." |

László Nemes mixes memory and desire unlike any other filmmaker today. His latest feature stirs us with the remarkable tale of Írisz Leiter (Juli Jakab), a young woman who returns, after years of apprenticeship in Trieste, to her native Budapest, the beating heart of central Europe in 1913, in hopes of working as a milliner at the famous Leiter department store her deceased parents used to own. Cinderella can turn into Bluebeard, with layers of civilised codes collapsing like a house of cards. Sunset demands and rewards our work.

Escaping into the past of 100 years ago brings us right here into the present, as firmly as only dreams, or ghosts, or fairy tales, or great cinema can do.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Wanting to be the chosen one, which turns out to be not what you expected the chosen one to end up as - I was trying to figure out where I had seen this elsewhere.

László Nemes: Me too.

AKT: And I couldn't.

LN: I couldn't either.

|

| Juli Jakab is Írisz Leiter in Sunset |

AKT: Really? The idea of wanting to be picked.

LN: It rings a bell.

AKT: It totally rings a bell.

LN: In a way in tales.

AKT: It starts out as Cinderella and turns into Bluebeard?

LN: Yes, definitely. In my childhood I was incredibly affected by tales, a lot of tales. Now I know that these tales were the changed version of things that were much more bloody and cruel. But they still retain a very strong and sharp nature.

AKT: That might be part of that metaphysical thing that is so often missing in movies today. And these tales have it because they are thousands of years old and there are elements in them that speak of something much deeper that is inside them.

LN: Something that is archaic and I like that. I really like that.

AKT: You have some of that with the feet in your film, don't you?

|

| László Nemes: "The hat store is for me a place of illusions, the way a civilization is etherizing itself. In a very nice way." |

LN: Okay? Possibly.

AKT: You have a character limping prominently. The devil is often depicted as limping. Later on we get a glimpse of some outrageous toe. I don't want to give anything away. Are these folktale devils entering the narrative?

LN: Maybe, I don't know.

AKT: Murnau's Sunrise is linked to your Sunset?

LN: It is linked, yes.

AKT: Just a quick aside to [Shawn Snyder's] To Dust [starring Géza Röhrig of Son Of Saul fame], which features clips from [Micha? Waszy?ski's] The Dybbuk from 1937. The director was an assistant to Murnau. Another little coincidence.

LN: Oh really? That's interesting, wow. Sunrise is about two people lost in civilisation and also in their own sins. And promises, there are between the despair and hope of civilisation. It's a couple lost between a sin and hope and redemption of their own couple. In a way it was between reality and a dream. I really could feel the relationship with this film which is also about closing and opening the eye. You know, closing and opening the eye.

AKT: The dream structure, the way it often feels when you dream - at least when I dream - you can get precisely this kind of a lost feeling. The tram getting you somewhere in the mist - who never had a dream like that?

|

| László Nemes: "I think if you don't give the answers, then also you can have something very organic building in you. And not dying immediately when you see it." |

LN: I know, it's between a tale and a dream.

AKT: Also, I like very much the way you give us terror. This sounds strange. I'll explain. When she [Írisz] is attacked, for example, it's terrifying.

LN: Yeah, I can hardly watch it, though I have seen it a lot of times.

AKT: It's very tough to watch and I was so happy when the scene was over and she escapes.

LN: Because whatever takes her has no face, you know. It's something that has no humanity. I am really interested in that aspect.

AKT: And that is so very, very different from so much that is out there! It's the opposite of what people want to shock you with.

LN: I know.

AKT: Just yesterday I stopped a film I had a DVD screener for at a scene where someone was characterised as a person who liked killing cats.

LN: It's easy to shock and exploit fears.

|

| Son Of Saul US poster for László Nemes's Oscar-winning film |

AKT: I stop watching these things immediately.

LN: I understand that.

AKT: The terror that you produce by the faceless entity and also when we don't know where the girls are going is different. I am asking you, why do I find this a constructive terror?

LN: Constructive? That's interesting. I have to think about that. Because I'm not interested in scaring you as an audience. I'm interested in transmitting something and sharing something.

AKT: A reality?

LN: It's definitely between reality and something in the mind.

AKT: Maybe the Real is a much better word, in the Lacanian sense.

LN: Something real, yeah. Something very real.

AKT: Like a hat shop. The film has its center in a hat store. What's in a hat store? I was thinking of the European-ness once again and history. Guy de Maupassant, the Käutner film Romanze in Moll, Walter Benjamin, the arcades and shopping.

LN: The hat store is for me a place of illusions, the way a civilisation is etherising itself. In a very nice way.

AKT: It's also violent. Dead birds.

LN: Dead birds?

AKT: On many of the hats. Many of them had feathers.

LN: Okay. I'm not sure they're real birds.

|

| László Nemes with Anne-Katrin Titze: "If you don't create things that have resonances beyond the film then it becomes too narcissistic." Photo: Jessica Uzzan |

AKT: They were. Stuffed birds.

LN: Stuffed ones, though it was not number one, I guess. I guess this extreme sophistication, hiding the illusion and the promise of a world that cannot see its own downfall is something that fascinates me.

AKT: Do you think we are at this point yet?

LN: In a way, yes. Maybe we lack the sophistication but we have the technology. And for the first time in history we are now producing communication in the virtual world that has no grounding in physical, chemical existence. It is entirely virtual. And we give ourselves to robots and our brains' powers are given to robots. So in a way we are full of illusions about ourselves. And in a much darker way, even darker than before the First World War, we are incapable of seeing our own desire for suicide. That's what I feel.

AKT: The question of modes of storytelling is important. Where does storytelling go?

LN: Today? I really believe that we have less and less room. I mean, there should be more room but there's less and less room for questioning the grammar of cinema and the way stories are told. In a way we are narrowing the path for the audiences and rely less and less on the audience. Because we want to feed them everything and just create a safe path for their experience instead of creating journeys.

AKT: The safe path is where the danger lies. It's not just boring, it's not harmless.

|

| Sunset US poster - opens on March 22 |

LN: No. Tell me about that!

AKT: It's like a lullaby, lulling audiences to sleep and making audiences believe that this is what cinema is. It's not going to touch you. It's not going to get to you. It's just one of the many distractions that you pick and choose and forget the next instant. And by that you are cluttering your brain with garbage.

LN: Yeah, I have the feeling too that we have definitely abandoned the creative freedom of the director and are worshipping self-censorship. And a narrowing of a path that should be the journey of the audience. Because we are giving them everything we have. We are more and more in direct communication, such as TV journalism. And less and less in the form of creating imagery that is in the mind.

AKT: In the mind?

LN: That should be in the mind. And less on the screen.

AKT: Yes, all the work you do when somebody tells you a fairy tale.

LN: Exactly! But then you remember the fairy tales. The fairy tales you remember, the movies in front of your popcorn, I'm not sure. That's the problem.

AKT: You remember them only if they do what the tales do. If they leave you the same room.

LN: Yes, I think if you leave the audience the possibility to use their imagination, and you don't deprive them of this possibility, I think there's a possibility for the audience to come out with something that's meaningful. Maybe not immediately, maybe two weeks after, but it's something that has to take time, something that has to infuse - that I think should be the mission of cinema.

AKT: That way it would also further communication because you could talk with somebody else who has seen the film but also saw a different film because it's a different person.

|

| Sunset at The Paris Theatre in New York Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

LN: That's how cinema should work. People who watched Blow Up in the Sixties, I guess that must have been this experience. Because Antonioni would not give you exactly the answers. And I think if you don't give the answers, then also you can have something very organic building in you. And not dying immediately when you see it.

AKT: It communicates also with your knowledge of other things. When your protagonist is in the boat, for instance, I wrote down Night of the Hunter and African Queen, as a mood memory aid for myself.

LN: Oh really? But it's also in Sunrise. That's something important. In a way I also use archaic imagery because I like it and it also has resonance. And if you don't create things that have resonances beyond the film then it becomes too narcissistic. If you do narcissistic cinema, that cinema starts and ends with the filming. And I don't think that's cinema.

AKT: I'm quite nostalgic about certain times and getting more and more so. The Belle Époque, for instance. I am craving these images.

LN: It's understandable because cinema is less and less that and more and more about digital technology. The more you can show, the less you can achieve.

AKT: Thank you.

LN: Thank you, so very nice to see you again.

Read what László Nemes had to say on TS Eliot, caves of darkness, the innocent and ominous in Sunset.

Sunset is in cinemas in the US.