|

| Girls setting their own agenda Photo: Fantasia Film Festival |

Jennifer Reeder is one of those prolific directors whose work crops up in so many different contexts that, contrarily, it often goes under the radar for mainstream viewers. This year she’s made a big splash on the festival circuit with Knives And Skin, the story of what happens to the people of a small American town when teenage girl Carolyn (played by Raven Whitley) goes missing. Reading the promotional materials, I tell her, I have to admit that I felt I’d seen this film before, but watching it was an altogether different experience. We connected whilst it was showing at Fantasia and she told me why she was attracted to the idea and why it’s not what people expect.

“I have a fascination with stories about missing teens. It’s not autobiographical. I never went missing as a teenager or had friends go missing. And although I am a fan of Twin Peaks it wasn’t coming out of Twin Peaks, it was maybe even more coming out of a story that inspired Twin Peaks about a missing girl named Hazel Drew. But it’s something about the missing girl in a small town being a kind of alternate horror scenario and it is really emblematic of the culture that we live in that really encourages violence against women or oftentimes considers young women, especially young girls, disposable. And so I wanted to build a film around that premise that was also a kind of a love letter to teen girl adolescence but also a kind of a love letter to films. It kind of spun out from there.”

|

| Dead but not out Photo: Fantasia Film Festival |

One of the things that stood out to me was how solid the teenage girls in the film are and how much agency they have. It’s something we rarely see onscreen.

“I’d made a bunch of short films leading up to this that utilise these same scenes,” she says. “That present girls that have lots of agency over their lives and why are really just trying to survive day by day as the adults in their lives have something like a second coming of age and can’t quite get their feet underneath them.”

I first noticed the film in the Fantasia line-up because I’d seen another film of hers, Signature Move, last year. They both make striking use of colour and costume, with visual characteristics that act like a signature for the director.

“When I was in school I was making films in an art school context rather than a film school context so my films have been, since the beginning, deeply influenced by visual art and colour and texture,” she says. “I consider filmmaking an art form. I like to tell stories through filmmaking but it would be impossible for me to ignore the art direction. I want to make something that is visually appealing and with the costumes and the music the art direction is narrative content and pulls the audience into that world.”

This film is also full of imagery commonly associated with femininity. I like the fact that the girls are allowed to be both feminine and empowered when too often cinema seems unable to reconcile the two.

“Right! And I actually set out to drench the film in femininity. I used all these pinks and purples and although I wouldn’t say that any gender owns pink and purple I think we can agree that pink and purple is femme!” She laughs. “I wanted the film to feel really feminine. I personally feel like I’m feminine, I identify that way, but I would never want my high heels and my dresses and my lipstick to portray anything other than I have agency and I am empowered over my life, you know? And I agree, I think that cinematically so many directors kind of ask their girls to choose. which one – and I don’t think that that’s accurate at all. I wanted to make a film that other girls and women could watch and really feel seen and feel empowered.”

All the Eighties music in the film also gives it something of the character of a John Hughes film.

“Yes certainly. The songs and the music that I use are parts of my own autobiography and I feel like this film is sort of a love letter to teen movies and certainly the John Waters – or John Hughes – roster is in there. Some John Waters as well! Even though now, rewatching some of those John Hughes films, we can see that they’re deeply problematic, at the time, as a teenager, it wasn’t really something that I could unpack. I just was really drawn to these misfit girls who still won at the end. They were misfit girls who had magic and they were the heroes of the story and that was very appealing to me.”

|

| Charlotte does things her own way in Knives And Skin Photo: Courtesy of Tribeca Film Festival |

There are a lot of misfit adults in this film.

“I like the idea that the teenagers in Knives And Skin are much more rounded than the adults. I think it comes from a couple of different things. I think we don’t do a very good job of allowing humans to evolve. It’s as though we can have one coming of age and that’s it. Actually I think that we as humans are constantly evolving and I think that adults should be allowed to make mistakes and to bounce back from those mistakes and learn from those mistakes but it feels like we’re allowed to have one coming of age and then if you have another coming of age it’s a mid life crisis or it’s a nervous breakdown. We use very negative language around it.

“I also think that, culturally, we don’t give teenagers enough credit for having agency and for being self aware, so I wanted to make a film where the teenagers really have all the answers and the adults are struggling for the answers and at some point they have to turn to the teenagers for advice and support.”

Does Carolyn’s disappearance provide a trigger for that?

“What I also wanted to do was to make a feminist film where there was a dead teenager at the core, because it’s such a problematic trope for so many other horror and thriller films that don’t deal very well with the object of the dead girl,” she reflects. “First of all I wanted to make Carolyn Harper have agency also so she’s a very wilful dead body. She’s not quite a zombie, she’s not quite a ghost but she has will on some level. And I wanted to make a film where her disappearance sends a very palpable kind of worry through the hearts of everyone in the town and that allows them to reach rock bottom, so that they can then pull themselves back up. I feel like all of the adults who make one mistake after another through the course of this film have a little moment of epiphany on some level. We see that they’ve turned a corner somehow or they’re asking for help or they’re understanding that they need to pull their lives together.

“The worry of the people in the town is also what animates the dead girl’s body and allows it to move around the town so it’s kind of a mutual relationship. It allowed me to make a film that had a dead girl as a narrative thread – I mean, it’s really Carolyn Harper’s story and she’s a very active character.”

The last person to see Carolyn alive is Andy (played by Ty Olwin), a boy with whom she’s out on a date which is ruined by his sexually aggressive behaviour. Jennifer says that she never considered having Andy kill her. “I didn’t want to make it his story. He also is not sure what happened to her.”

|

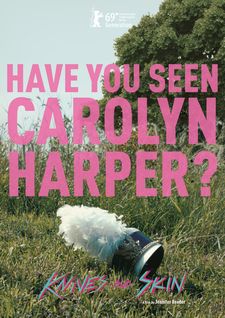

| Knives And Skin poster |

Does the fact that we see him behaving so unpleasantly but not killing her help to emphasise how damaging such behaviour can be – the kind of behaviour that’s often excused?

“A lot of girls are dealing with all these things around them including peers who have no interest in respecting consent and no interest in respecting boundaries. And that can damage a person physically... We are looking at rising suicide stats, rising stats of drug and alcohol abuse and eating disorders among young girls and it’s not getting better. We’re not in a post-#MeToo, we’re still in that and I think adult women are sometimes better equipped to confront the men in our lives who are violating consent but for a 14 or 15-year-old girl, who really still is a child, it’s a very difficult thing to unpack that.

“With Andy, who is the one who’s with her at the quarry before she goes missing, it also felt important that I don’t focus too much on him in the story but that he also gets called out for his bad behaviour and that potentially, when the cheerleader gives him his jacket back and he walks through the town with this message on the back of it, that he’s outed, his behaviour is outed, and he hopefully will have a chance to learn from that and become a better man. Because I do think that we live in a culture that tells girls not to get raped but we still don’t tell boys not to rape girls – or not to rape people. And so I also want there to be a message in this film that say ‘Boys, you have to behave better.’”

The film enjoyed a warm reception at the Berlinale earlier this year, attracting positive responses from packed audiences of young people, she says. So how did she feel about it being selected for Fantasia?

“I was thrilled! Fantasia has such a great reputation. But I was also curious as to how it would be received by genre audiences because it’s really genre-adjacent, you know? I mean it’s not a horror film, it has horror elements. It’s not a thriller, it has thriller elements. it’s not speculative fiction even though it has these kind of magical realism moments. Really it’s kind of” – she hesitates – “I call it a Midwestern Gothic teen noir. Really it’s a story about female friendship as a survival strategy. It’s a story about adult coming of age. It’s also got music in it but it’s not a musical. And even before it got to Fantasia it was at Tribeca where it was programmed in the Midnight section, which is also a genre section... and it’s going to Frightfest. I was kind of unsure about how it would be received at first but I really appreciate how it’s been welcomed.”