|

| The Mountain director Rick Alverson: "There's a lot of parallels between the lobotomy and filmmaking." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

In the first instalment of my in-depth conversation with Rick Alverson on The Mountain, co-written with Person To Person director Dustin Guy Defa and Colm O'Leary (The Comedy), shot by Lorenzo Hagerman (Entertainment), starring Jeff Goldblum and Tye Sheridan (Alexandre Moors's The Yellow Birds), with Hannah Gross (Michael Almereyda's Marjorie Prime), Udo Kier, and Denis Lavant (a Leos Carax and Emmanuel Bourdieu favourite), we discuss what "interrupting the trigger" means to him, "parallels between lobotomy and filmmaking", a Django Reinhardt number, and the role the threshold move plays. Rick confided to me that he is a "big Perry Como fan" and that he was "reared on all that Disney stuff" when I brought up a scene that reminded me of Snow White.

|

| Rick Alverson on Denis Lavant: "He's more poetic than I am." Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

The Mountain follows a boy called Andy (Sheridan with wonder in his eyes) from life with his father (Kier), a demanding ice skater, to becoming the photographer/assistant of Dr. Wallace Fiennes (Goldblum), traveling lobotomist, on to meeting shaman Jack (Lavant) and his daughter Susan (Gross). The encounters on the road resemble those of an ancient fairy tale and the heightened, faded images are beautiful and eerie.

There are casually folded-in musical numbers: a Busby Berkeley or Matthew Barney inspired ice rink formation, Goldblum tap-dancing at a bowling alley, Lavant being taken over by a trance at a séance "Out of the body. Into the body." The film effects in waves. This isn't Oz, the boy isn't Dorothy, but The Mountain does on some level feel like a vessel of Alverson's thoughts about the wizard and his false promises, and tinfoil gifts - the charade of a perpetually inspiring dream of the new world that never ends and never existed in the first place.

Anne-Katrin Titze: The first time I heard about your film was in November 2017 from Denis Lavant when he came to New York right after filming.

Rick Alverson: Oh, right! You know him?

AKT: I met him for lunch then and when I asked him what The Mountain was about, he gave me the explanation "the threshold move".

|

| Rick Alverson on Denis Lavant's Jack in The Mountain: "Ah, yes, it definitely is a sort of exposed deity kind of character, like the end of Wizard of Oz." |

RA: Ha, ha!

AKT: I wasn't sure if this was a verb or a noun. I asked him, is it a move? Or does the threshold move? He kept it mysterious.

RA: He's more poetic than I am. But it's very much a noun. The target, you know. The moment of arrival.

AKT: That is the threshold move?

RA: Yes.

AKT: So this is at the core of your film?

RA: I think so. I like that line. Also I think a lot about the threshold of the screen and content and form. And this idea of moving across the threshold into the content and then pulling back into the form and being aware of ourselves in the room and questioning what we're seeing and imbibing.

AKT: The question of seeing and the eye are of course also at the centre of The Mountain, because the eye is the entry point where the lobotomy takes place.

RA: Sure, the access of the procedure. I mean it's almost a silly metaphor. For me the idea that the eye is the threshold of access for the procedure, it's also part of that threshold of access into a film. And that awareness. There's a lot of parallels between the lobotomy and filmmaking. Consumer film construction.

|

| Rick Alverson on Jeff Goldblum's Dr. Wallace Fiennes: "For me the idea that the eye is the threshold of access for the procedure, it's also part of that threshold of access into a film." |

AKT: That we get a lobotomy with certain films, by watching them? To boil it down?

RA: Not directly, but if you play the metaphor game, the idea of engineering passivity in a population.

AKT: True.

RA: It's core to my consideration of the medium. Thinking about it, meditating on it, working against that.

AKT: A lot of the actions concerning the lobotomy, I suppose, are based on Walter Freeman [who performed transorbital lobotomies by severing the connection at the prefrontal cortex with an icepick through the eye - his road trip in the 1950s around US state hospitals was called Operation Icepick.]?

RA: The architecture of this moment in time and the fall from grace in the procedure itself is based on him. But it just uses sort of the veracity of that history and then the rest is fictionalised. It certainly isn't Freeman in the film.

AKT: You kept the initials.

RA: Just kept the foundation, a sort of knowing that it conforms to a particular moment in history. It has a sturdiness for the exploration.

|

| Rick Alverson: "I think a lot about the threshold of the screen and content and form." |

AKT: The 1950's hold a sturdiness because of now? This moment in history we are living now, where people are ….

RA: … romanticising?

AKT: Romanticising it, trying to recapture some vague invented idea of the Fifties, but forgetting about the war that made them, for instance.

RA: There's a lot of the idea of wilful ignorance, and engineered ignorance, and the idea of suppression of our awareness of limitations. They are very similar to that time now. We're moving sort of into this refraction, this crazy hall of mirrors. It's like a meta version of what was occurring in the Fifties. It's like hitting the front page every day now. And that period is obviously the period that Make America Great Again refers to.

This period of disconnect from the realities and the possibilities. You know, corporate culture and exploiting people's belief in the infinite. And that's taken us into a frightening doorstep of something that is very frightening when we've exceeded all of our capacities as a civilisation. The raw materials, the capacity of the environment to withstand what we've done. These are sort of where the wilful ignorance continued on.

AKT: The environment in The Mountain, you even call it The Mountain, is nature. But the way you show nature is almost in a German Romanticism kind of way.

|

| Denis Lavant rotating the cube at Astor Place in New York Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

RA: Yes, it's like a church, sort of.

AKT: It's sublime but rotting at the corners, it's paling, it's fading. The images are beautiful, too. I as a viewer felt almost poisoned by them, by the bitter nostalgia coming up.

RA: Right. I'm very interested in that trigger. But I'm also interested in interrupting that trigger.

AKT: You did.

RA: The idea when we move into that very safe space. And I'm not saying that there's no place for being comforted. Me as much as anybody wants to be comforted. But we are a very privileged society, as much as Europe.

And the idea that this constant exposure to reinforcement and comfort and validation is beneficial to us, doesn't just increase this distortion of reality about the conditions of the world, is, I think, a problem. So I think that does need to be interrupted.

But the film is what questions narrative too. Both the narratives of these blind kind of narratives that Fiennes, the doctor, for instance, is trying to reinforce with the photographs and with proof. And with this sort of idea that he's helping people and that they're well and they're moving on. And the ramifications are just falling like a wake in a bloodbath and a wake and it's behind him. That he can't bear to look.

AKT: He moves on. He has to.

RA: This is engrained in us to this day. It's still that tragedy is still occurring.

AKT: In your film, there is one scene that reminded me of Disney's Snow White, when the forest seems to be turning against her.

|

| Reda Kateb played Django Reinhardt in Étienne Comar's Django Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

RA: Oh right, I see that. I was reared on all that Disney stuff when I was young.

AKT: Disney invented that moment. It's not in the Grimms' tale that the movie is based on. This is a scene about her fear, Snow White's legitimate fear of the world projected onto nature. I was surprised to be reminded of it. The Mountain is one of the most unpredictable films I've seen recently.

RA: Good.

AKT: I saw The Mountain in May, so please forgive me, I wrote down this question and forgot if it was part of the film or my thoughts. "Is this what God looks like?" is not a line in your film near the threshold, is it?

RA: No.

AKT: Then it was my thought when Denis Lavant is dancing his wild dance.

RA: Ah, yes, it definitely is a sort of exposed deity kind of character, like the end of Wizard Of Oz. The curtain's pulled back and there's a deformed pseudo-omniscient kind of presence there that is actually just a befuddled, broken harbinger of things to come.

AKT: And that's what God looks like. I am not often during a movie tempted to ask myself this question, and then forget if it was me or the film who asked it. In the end, over the credits you send us off with Home on the Range. How do the music choices fit into what you just explained about comfort and discomfort?

|

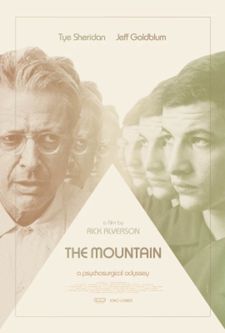

| The Mountain poster |

RA: I'm a big Perry Como fan. I was raised on him. I find it very comforting. I'm mixed up in there to some degree. The idea of arrival, the romanticised idea of arrival, that is actually impossible but that we have this perpetual faith in, particularly as Americans.

Once the world was fully trod, it just sort of spilled back from the West Coast and then was packaged up and sold to the world as a brand. The brand of the Utopian ideal of unlimited possibilities and endless potential.

AKT: That's all packaged up in the idea of the home on the range?

RA: To some degree, yeah. The nostalgia of that and the frontier. But I particularly love that rendition because it's full of a kind of melancholy.

AKT: The Django Reinhardt number is also full of melancholy. Melancholy is a good word for what is going on. The object is still there but what made you desire it is lost, and so is the desire itself - that's one of the definitions of melancholy.

RA: Right, wow.

AKT: Does that make sense?

RA: Yeah, I think of exhaustion. Sort of padded, kind of like with an act of self-soothing.

The Mountain is in cinemas in the US.