|

| Hugh Grant and Andy MacDowell in Four Weddings And A Funeral. Mike Newell: 'They were all so gorgeous when they were young' Photo: © 1994 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved |

One of those directors who never watches a film he made after he’s made it, Mike Newell once upon a time breathed new life into British cinema with his box-office-breaking and award-winning romantic comedy Four Weddings And A Funeral, now 25 years old. After this now-cult film, he moved on from the formulas of feel-good movies to Hollywood blockbusters of the likes of Harry Potter And The Goblet Of Fire (2005), one more film that has reached cult status according to pop culture standards and yet another that has marked an entire generation of youngsters.

A Cambridge graduate, Newell began directing at 22 and worked on various plays for TV. His springboard to international success was the TV film, The Man In The Iron Mask (1977), which was ultimately released as a feature film. He then directed Dance With A Stranger (1984), that won the Prix de la Jeunesse in Cannes, The Good Father (1985), Enchanted April (1991), which won two Golden Globes, and Into The West (1992). In the wake of the success of Four Weddings and Harry Potter, Newell showed his directorial sensitivity and versatility as he juggled deftly between genres with films such as An Awfully Big Adventure (1995), Donnie Brasco (1997), Pushing Tin (1999) and Mona Lisa Smile (2003), also boasting Love in the Time of Cholera (2007), Prince of Persia: The Sands Of Time (2010), Great Expectations (2012) and The Guernsey Literary And Potato Peel Society in his back catalogue (2018).

We caught up with him at this year’s Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival, where he served as President of the Official Competition.

|

| Director Mike Newell in Tallinn Photo: Courtesy of Tallinn Black Nights |

Mike Newell: Well, as you say, it’s 25 years and about this time last year, we set up a little 12-minute film for Red Nose Day and absolutely everybody came back. Sadly, there are some who are dead, but all of the original actors came back, all of whom are now stars of one kind or another. It made quite an extraordinary number of careers, that film. They were all so gorgeous when they were young. Now, they’re just like me; they’re kind of lined and craggy. It’s a terrible indictment of getting older, but we had a very good time together and it was lovely to see them and to remember them how they were when they were young and lovely. And it was a very affectionate thing.

The film was shot very fast – 32 days – but given what it was and that there were four weddings and one funeral, it had an enormous amount of extras apart from anything else. It cost nothing; it cost under three million quid and you would think that those circumstances might make people impatient with one another. I think there were probably greater tensions between me and writer Richard Curtis and producer Duncan Kenworthy than there were between any of the people who are acting in it. I remember we got ill-tempered with one another from time to time; we used to fight about what was funny and what was not.

Do you think it has aged well?

MN: When we were going to do the little Red Nose Day film, the original producer said to me: “We must all watch the film again” and I watched it again and there are things I would have done better, things that I would have done differently - but mostly it hangs very well together. It survives well simply because it’s funny and Richard wrote a wonderfully funny script and you forgive it everything because it makes you laugh.

|

| Jack Thompson in Bad Blood. Mike Newell: 'I had a roughish ride starting in the movies and that was a great relief' |

It has become such a hit and it’s a cult film now. Why do you think that is?

MN: It’s because of what it’s about. When you see the title and you look at the publicity and the poster, you think: “Oh, I see, it’s a romantic film. It’s about love.” It is about love, but it’s not about romantic love. It’s about the love between friends and, therefore, that’s a great commonality; that’s a great thing that people have in common. Everybody has friends, everybody is amused by their friends, exasperated by their friends, intensely related to their friends and it’s that that’s underneath the whole film. And, of course, that is beyond fashion, that’s beyond temporality, there’s no time in that, it’s universal and forever and I think that’s really what it’s about. That’s why it’s lasted and has become a cult.

When it was made, 25 years ago, how characteristic of its time it was?

MN: It’s really interesting because it’s very English; everybody in it apart from Andy MacDowell is British. But there were no tensions in the society at home that there are now. Things are very unpleasant in England now because nobody agrees and everybody distrusts everybody else. We all believe that there is going to be a bad outcome in the election and we distrust our politicians and particularly the fact that Parliament is being set against the political parties. It’s a very disruptive time. Plus, we’ve had the recession… And so, things are negative at home now – negative and grating.

Back then, none of that was true. There was a new way of looking at the country, which was that we can do it, we are young… And the big thing was that we were young; the politicians were young, Tony Blair was young and I think that was a huge factor in it because I know that a great many young people felt that the film spoke for them. They felt that Hugh Grant spoke for them – he was a representative of their generation. He was gorgeous to look at, he was very intelligent, he’d been to an immensely good university and he was a person who you hoped to be as what actually a lot of those characters who are all English eccentrics of one kind or another are. So we looked at those people and we said: “We know those people! They are us!” And they may be crazy, but they are happy crazy. I think that that meant a great deal.

And now, there’s a TV show in America…

MN: I heard about that, but I haven’t seen it! They haven’t shown it to us; they haven’t talked to us. I had no idea that it was being made until quite recently. I assume that Richard knew that it was being made because he has to sign off on the idea, but he didn’t say anything to us.

What do you think of the romcom genre today? It’s not what it used to be, it’s very different and there is no place for it any more.

MN: I think that one of the big things that’s changed is that because of that film, because of Four Weddings And A Funeral, the people who decide to make films, the studios, the producers, etc. think of the romantic comedy as a cure all. It solves everything, right? And so they are, in some ways, films quite cynically made and sometimes they are made out of desperation: “What can we do? What can we do? So romcom!” Well, it wasn’t like that… What it was like was that nobody had done a film like that back then for probably 30 years and they certainly hadn’t done it with an English look at that kind of subject.

|

| Into The West. Mike Newell: 'It’s very funny from time to time, it’s very wild from time to time and it’s written by an extremely good Irish writer' Photo: © Miramax Films. All Rights Reserved |

You mentioned Hugh Grant before, and I’d say that the film made his career.

MN: It made all of us! It made me, it made him, it made Richard… But yes, you’re right it did.

But it also sort of boxed him in the romcom genre for a long time.

MN: Yes, for a while! But now, he’s fought his way out. He made a television show (A Very English Scandal) about a corrupt politician who is gay, who has a gay lover who starts to cause him trouble and so he decides to have him killed and it goes disastrously wrong! It’s a real case. It has a tremendous cast and a brilliant director. It’s very funny because really in the end, it’s the story of how the English always screw it up.

Would you agree with the notion that Richard Curtis is the gatekeeper of the romcom genre?

MN: He is right now! Sure! He has been for 20 years. That’s what he does. That’s his thing. For me, it was different. I was invited to follow up Four Weddings And A Funeral, but I didn’t want to do the same thing twice and, of course, the trouble with follow ups is that they tend not to be as good as the first one and you go on a downward incline. In fact, they avoided that. The man who made the second of those films (Roger Michell, Notting Hill) with Hugh is a marvellous director and he made a very successful film and they got Julia Roberts and it was all great. But Richard is the gatekeeper for the romcom. How long can he make it last? I don’t know!

Would you make a romcom together now, but like the good old ones?

MN: I don’t know whether I could do it. I am an old man now. Back then, I was much, much younger, but maybe I could, but that’s not something that’s on my slate right now.

But, for instance, hypothetically speaking, if you were to direct a romcom and Nora Ephron were to write it, would you make it?

MN: I think that what I would say is that if it were Nora Ephron and she was on song and she was writing well, then you bet! Because what would happen is that particularly Nora Ephron, who’s got that sharp Jewish New York sense of humour, you wouldn’t find that it would get soggy. But the problem with romance is that it gets soggy and so the answer to that is if it’s Nora Ephron and if it’s not soggy, then you bet.

Do you have any favourite film of yours that you made, one that you are particularly proud of?

MN: Inevitably, you do… I’m very fond of a film called Bad Blood that almost nobody has ever seen because it was made in New Zealand, 30 or more years ago and it was the first time that I had felt free to make a film in exactly the way that I wanted to. My background was that my very first film, which was successful, was made for an American television company which was then translated into a feature film. They thought that it would work as a feature film and so it did. And that was a film called The Man In The Iron Mask and it had lots of big deal Hollywood actors, both British and American, and then I went to Hollywood because that’s what you did, because there were no indigenous films being in England at the time I was doing it. English cinema has always been a very fragile thing. And I got a job. And I was very happy in the job, but it was perhaps a film that I shouldn’t have made. I am not sure. Indeed, I lost control of it. They took it away from me and recut it.

In a long life, everything happens to you… And so, I’ve been fired and I’ve been replaced… So I was jaundiced, I was discontent with that way of making films and then a guy I had known in British television, Andrew Brown, who in fact was a New Zealander said that he had written a film and would I have a look at it and I had a look at it and he’d written a film about a famous murder case in his own country. It was very strange because it was about a society that I didn’t know. It was set in what was a clearly foreign part of the world.

New Zealand is as far as anything you can get and off we went and we managed to get somebody to give us the money for it and we made it. Right there. And it was freedom. There was nobody looking over my shoulder. There wasn’t a studio hanging over me and I felt absolutely free and I felt able to do whatever I wanted and indeed sometimes behaved very badly because I behaved in a slightly paranoid way. But at any rate, it was closer to a story that I really wanted to make and felt that I could make than any story I had made so far outside of television. I had a roughish ride starting in the movies and that was a great relief.

And then, there is another film that I made in Ireland, which I am very proud of, which is called Into The West. It’s about gypsies and a folk story which comes to real life. It’s very funny from time to time, it’s very wild from time to time and it’s written by an extremely good Irish writer. I made it for Harvey Weinstein who at one stage wanted to fire me, but I managed by my native political skills – I am, after all, British – to avoid being fired and stayed with the movie and made the movie that I wanted to make. It was very difficult. But the thing about Harvey is that I think Harvey had a disease which grew progressively more severe. I made two films for him and I worked with him before the disease had started to go bad.

You didn’t know anything?

MN: Everybody knew. And anybody that tells you that they didn’t know is a liar. But what we didn’t know, because it wasn’t I think true at that stage, was that it was as compulsive as it then became with him. He hadn’t been at it long. They were very demanding as a company and they had a relationship with one of the people who was important in the film that meant that firing me and having somebody else take over from me may have always been part of a plan because I took over from another director who they had been unhappy with.

And I like Donnie Brasco, too.

Between Four Weddings And A Funeral and Harry Potter, you have participated in the creation of two important British but also international titles in film history and pop culture that have marked two generations. Can you talk about that?

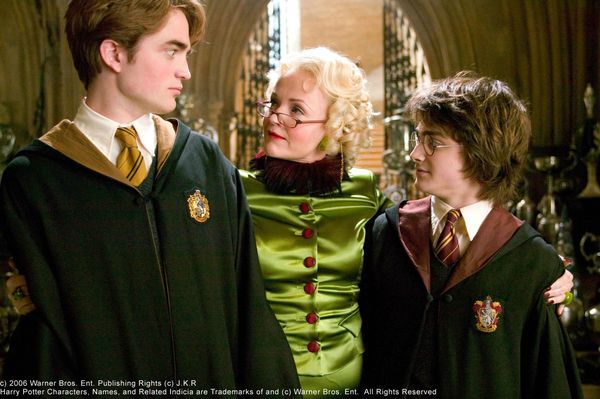

MN: Well, I was very proud of Harry Potter because Harry Potter, for me, has got all the elements that it had to have: it’s got the kids; it’s got the magic; it’s got the spells… The one thing it hasn’t got is that awful bloody game, Quidditch – at least I didn’t have to do Quidditch! I hated Quidditch! I never understood it! All I had to do was the opening ceremony of the Quidditch World Cup; well, that’s easy. The kids were older, so there was teenage flirtation, there was Harry’s first kiss, there was all sorts of stuff like that, but for my money, the two best things in it were this kind of classical simplicity of story where what you could say is that: Are the bad guys going to get Harry? If they do, all they want is three drops of his blood. That’s all. What they want it for, we don’t know… Immediately, that’s a good story. And the other thing about it: emotionally, it was that, of course, there was the romance and all of this stuff, but there was also death and the bit of the film that I was proudest of was that I cast RPatz – Robert Pattinson.

So, you made another career…

MN: I made another star… which is great! I’ve made four or five in my time! But the point about Robert Pattinson was that he’s a type of character that the English will understand because he is the fighter pilot who is doomed. He is the hero, he is the handsome one and as he steps in the spitfire, you know he is going to get the shit shot out of him and, indeed, that was the case. The actor who plays his father carried the weight of that because of the end – you meet the two at the beginning of the story and you see them both again and they crash back into that arena and the father thinks that he’s won. He thinks that his adored, handsome, glorious son has won. He doesn’t know that he is dead and he then realises that he is dead and he howls. I invented that and I am very pleased with it.

You have made a film with Netflix, The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society. Can you talk about that experience?

MN: The film was about this: is this girl going to discover herself or is she going to go on writing daft comedy novels for middle-aged middle-class ladies who all flutter at her? And in the end, she’s got nothing to write about. It’s not real to her. And the story, for me, is the story of somebody who discovers themselves and discovers that to have gifts, a talent is a burden, is heavy, it demands things of you and there is this wonderful line, which I found very moving where the publisher goes to her and says: “Have you written it?” and she breaks down in tears and says: “What if I’m not good enough?” and I feel like that every time I wake up. So that film is private and it’s about somebody who finds themselves.

Netflix is weird because they are tremendously welcoming, tremendously helpful. You have these huge Skype conferences with them sitting at tables as long as this room in California and you sitting at a little table in London and they tell you what they are going to do and what the publicity is going to be and they tell you about how marvellous the film is and so on and so forth and then they let slip that they’ve got a slightly different idea about the movie and you say: “Hmmm.” They say it’s a romcom and you say: “No, it’s not.”

What are your next projects?

MN Well, I’ve got two or three. I’ve got a very good script, which is by a writer whom I nearly worked with before and I nearly made a movie called The Girl With The Pearl Earring. Well, that was going to be me and then there was a tremendous falling out about casting, about money and I left the film, produced and written by the husband and wife team who have now written a script about the British atom bomb in 1947. The second one is a story about a German tennis champion in the 1930s who is an anti-Nazi and it’s a true story. And then, I want to make something about the amateur dramatic company where my parents were from their teenage years and they built. It still exists, it still has its theatre and they were the people who invented it. I want to see who they were when they were young through the theatre.