|

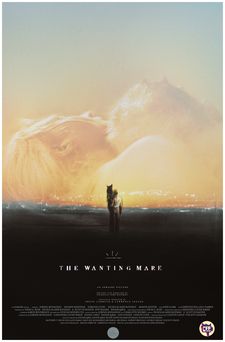

| The Wanting Mare |

With its striking locations and beautiful light, Nicholas Ashe Bateman’s début feature, The Wanting Mare, looks as if it was show somewhere really exotic. In fact, it was made almost entirely within the confines of a warehouse. The film, which had its première at the Chattanooga Film Festival, is the product of a new generation of technology that’s constantly evolving – and, of course, of Nicholas’ imagination.

Joining me from his home in New Orleans, where he was sitting beside one of the computers that brought the film to life, Nicholas told me that he’d ideally like to live somewhere more like Scotland, where I am. I responded that his fantasy world of Anmaere, for all that the weather there is hot, has a very northern feel about it.

|

| Nicholas Ashe Bateman |

“That was a bit of a challenge visually,” he says, “because so much of what I wanted to make, in terms of where the film was, felt very northern. Certainly its largest influence is Wuthering Heights. I wanted to have moorlands but it had to be kind of arid. people would say ‘There’s a lot of wind for somewhere where it’s hot.’”

I ask him if the world and the story set within it were what came first, or if that was the technology he wanted to use.

“It was the story,” he says firmly, and acknowledges that that was a hard sell, “probably because it seems illogical! It really has been the past eight years, a constant process. it’s something that I was interested in when I was a kid. I was a child of DVD special features and that early 2000s visual effects – Lord Of The Rings and those things – were so exciting to me, they said me on a path. You would hear people say things like ‘You know, one day somebody’s going to be able to make a movie in their bedroom.’

“It was the story. I worked on other things and it stuck with me and I kind of carried it around with me, writing it, trying to figure out how to do it.”

I tell him that I’ve heard he wants to set more stories in the same world.

“I would love to. I really love the idea of the boundaries of it an I also like the idea of committing to a single thing. I don’t really think I’m going to be able to make, like, a bank heist movie, regardless.” He laughs. “But just saying everything is in this place is really fun to me. Much as I love this movie, this is something I wanted to make when I was 22, and I’m 30, and I’ve been writing again in the past year and a half and thinking about how t grows. I love the idea of having to fight with one thing.

Jokingly describing himself as a failed painter (he actually did matte painting work for Alex Huston Fischer and Eleanor Wilson’s alien invasion film Save Yourselves!), he observes “All my favourite painters, they have their one studio and they wake up and work on their few things. They’re not like ‘Well, I did this house before, so now I need to do a waterfall.’ That question of range, I think, is only for filmmakers.”

I suggest that his preference reflects the way that some painters return to the same subjects again and again.

|

| Jordan Monaghan, Nicholas Ashe Bateman, David A Ross and Z Scott Schaefer at work Photo: Rexon Arquiza |

“Pretty much,” he says. “I’m a huge Andrew Wyeth fan and his return to, basically, three places that seem to interest him. I don’t know why these places [in Anmaere] have a hold of me and I don’t know what they contain. At a certain point everything is talking about time. My interest in the question of time, certainly in this movie, is how it moves so quickly. I think the movie has that feeling – hopefully – of we were just here,, you know? The only real witnesses to those things are the places. I think that is usually my connection to fantasy: these things are older than us and we we are, on some days, doing well; on other days not as much.” He laughs.

I remark that it’s unusual for a filmmaker or artist to take on a subject like this so early in life, and also that it must be really tough to pitch a story that takes place over 60 years – something that’s not very studio-friendly.

“I’m the youngest of three children, and the whole branch of my family, aunts and uncles and cousins, I’m the youngest of all of them, so I think there was a feeling of arriving into a world that had already been going and trying to figure out what it was like before I was there. I would constantly get in trouble when I was a kid because I would go through all my siblings’ things. I have always been really, really preoccupied with the idea that we’re all not here for a long time, and I just think that’s what it’s all about.

“I’m very interested to see what this movie looks like when I am older. Even now I feel very distant from the person that initially wanted to make it.” Back then he imagined it like a Nineties French film, he says, with “something sweaty and dirty and quick about it.” it had a wild intimacy which he feels became more muted over the years.

Getting onto my second point, he assures me “There isn’t a single dollar in the movie that has been financed by any form of Hollywood. I don’t know many people who are doing the traditional thing. Early on, someone offered to buy the script, when I was living in my car. Somehow – I don’t know how I did it – I said ‘I can’t do that because this is really all that I have.’ But that single attempt by someone allowed me then to go to other people and say ‘Look, I’m not making this up, I really think some people think this is a worthwhile idea.’

“The first chunk of the movie, which is myself and Jordan Monaghan [acting], that whole sequence we filmed with under $35,000. That was all the money that we could raise and, I think, a little more than a third of the movie. That was all that we had so I had no idea that we would even be able to finish the movie. We didn’t have a crew of more than six people. We were driving around getting as much as we could naturally. So that was terrifying! it was really scary. The feeling of starting without knowing if we’d finish created a terror that were going to be judged on what we made with the least amount of resources.

|

| The Wanting Mare poster |

“We were very lucky that a bunch of wonderful people, mainly in New Jersey, were like ‘You wanna make a movie? This sounds great!’ So if you look at the credits there’s like ten crew credits and 35 producer credits.”

How did he keep his team together in those circumstances?

“I’ve geared most of my life, in the past decade, around independent film,” he says. “When you’re making movies for no money and no-one is getting paid and you’re living in garages and offices, you learn so much. It’s like, okay, how do we make this worthwhile? People are giving so much of themselves.”

It helped, he says, that he did this kind of work on other people’s films before his own. He’s worked with some of the same people for years – DoP David A Ross, gaffer/VFX artist Z Scott Schaefer and camera operator/VFX artist Ger Condez, all of whom also have production credits on the film. He’s keen to highlight the help he received from production designer Cassandra Louise Baker and art director Duncan Bindbeutel on the second phase of the film, plus the office crew who worked behind the scenes – the sort of people who never get to do interviews and, he feels, never really get the attention they deserve.

For him, he says, the big question is “What does this person want to do? Am I giving them the best venue to do it?” He wants them to be in a position to say that this was the best work they could do.

“I liked in the office that we made the movie in with Zack and David for about three and a half years. I remember thinking ‘It seems insane to say now but I think this is something we’re going to look back on and think was the best,’” he says. “Because it’s definitely never going to be like this again. If it doesn’t work out, nobody’s going to give us any money ever again. If it does work out, no-one’s going to let us just stay in a warehouse for three years and say ‘Finish when you’re done.’”

He apologises for an intervention by his dog, who has been sitting on his lap. As a fairly new filmmaker, he’s not yet used to doing interviews, but I assure him that dogs getting involved is by no means rare. He explains that this particular dog was also sitting with him through much of the filmmaking process.

It’s clear that his team, lacking the budget to hire outside help, had to pick up the skills they didn’t have to begin with along the way. How did that work out?

“It was a daily process of how do we do this?” he says. “We basically knew just enough to be able to be there on the first day that we wanted to film something. Then it was like ‘Oh, right – it took us half a decade to get to this point and now we’re on day two – where do we go from here? Then the other thing that happened, which was a challenge but also good, is that once we did learn something then we were doing that better, and then the other stuff that we had finished that was less skilled became more problematic. We had to go back and change the whole thing. That’s partially what took so long. I have probably redone the entire film who knows how many times.”

Coming up: Nicholas Ashe Bateman on how technology is changing and why he wants to do something different with the fantasy genre.

The Wanting Mare will be available to rent or own on digital HD on 7 February 2022.