|

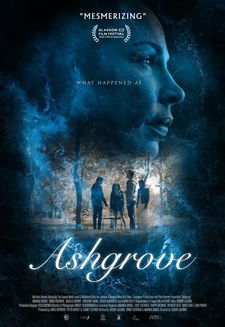

| Ashgrove |

Some of the best science fiction has been predicated on the consequences of a simple thing which we all rely on suddenly becoming unavailable. In Ashgrove, a change in the nature of water creates a terrible dilemma. Drink too little, and one will dehydrate. Drink too much, and one will die. With the entire population gradually becoming more ill, there is a serious threat of extinction. Jennifer (Amanda Brugel) is in the front line of the response. After months of ceaseless work, she feels she’s on the brink of a game changing discovery, but she has driven herself to the point of exhaustion and simply cannot maintain the mental discipline needed to get to the next stage. As such, she’s ordered to spend a few days recovering in a secluded farmhouse.

As well as failing to look after her mental health, Jennifer has been failing to look after her marriage to Jason (played by co-writer Jonas Chernick), who has tried to stand by her but is only human himself. With an unresolved tragedy in their past, the couple try to use her downtime to get themselves back on a more even keel. Jonas wants to teach her to relax, but is that possible in the face of such a catastrophe? As time goes by, the situation begins to make her paranoid, convinced that something else is going on. It’s a small film with big ambitions and it’s screening at this year’s Glasgow Film Festival. I met up with Jonas to discuss it and, as we waited for his co-writer and director Jeremy LaLonde to arrive, he told me how the idea behind the film first developed.

“Jeremy and I were in a car driving from one Canadian film festival to another, from Calgary to Edmonton, with our last film, which you've seen: James Vs His Future Self. So we started talking about like, ‘What do we want to do next?’ And we agreed, on this car ride, that we wanted to do something entirely different. We've both done a number of comedies, we love comedies, but we wanted to do something new and do it in a way that we've never done before. So we started pitching ideas back and forth. And I pitched him on the idea that, as an actor, I really am interested in doing a very intimate chamber piece. I think with the idea I gave him was a couple struggling to save their relationship over the course of one day or two days, and just we just stay with them. And it's intense and funny and heartbreaking. And he said, ‘Yeah, that sounds that's interesting. Let's, let's look at that.’

“ ‘For me,’ he said, ‘if I'm going to direct it, the stakes have to be there. That works for me if the world is ending outside their door.’ And I thought, ‘That's not what I'm going for.’ But the more we talked about it, the more we got excited about this idea. By the time we were finished this three hour car ride, we had this idea. We came up with this water crisis. And this was months before anybody had heard the word ‘Covid’.”

Jeremy enters at this point and makes himself comfortable as Jonas continues.

“From there, he and I developed it a little bit more, but then we immediately brought Amanda in. We thought, ‘Who do we want to work with? Who's the actress that we most want to work with?’ And we both worked with Amanda before, and so she was the first on our list. When we got to Edmonton, Jeremy made a call and said, ‘Do you want to create this with us and go on this adventure with us?’ And she said yes. And from that point the three of us developed the characters and the world and the back stories. Amanda was integral and really built her own character from the ground up.”

So when they did hear the word ‘Covid’, how did they feel? Did they panic, or did it bring something extra to the film?

|

| Amanda Brugel and Jonas Chernick in Ashgrove Photo: Courtesy of Glasgow Film Festival |

“Well, you know, I don't think anything changed from the way that we envisioned it,” Jonas says ”The fact that it was about a pandemic, while a pandemic was happening at the time, just felt very timely. I mean, you know, it's hard. I don't use the word ‘pandemic’ when I describe our film, because I say that that the world is experiencing a water crisis, but the similarities are there, for sure.”

“The idea of Amanda's character being a metaphor for first responders like that definitely wasn't part of the planet strategy,” adds Jeremy, “but it's awesome that it relates to that in a way – I hope in a positive way.”

Jonas nods. “You think about the scientists in the labs that the drug companies who were tasked with ‘As quickly as possible, we need a vaccine, the faster we have a vaccine, the more we can save the world.’ So there was a handful of these scientists holed up in these labs for months with the pressure of the world on them. And, you know, we don't know who those people are. Nobody talks about the the lead Johnson and Johnson scientist, or whoever it was at, you know, Pfizer, AstraZeneca. They were people trying to save humanity, because in the early days, we didn't know that we weren’t all going to die from Covid. You know, it was very scary. So I guess in a way, accidentally, this is the sort of the story of the first responders, as Jeremy says.”

We talk about the wider experience of people in high pressure jobs and the difficulty of balancing societal responsibilities with familial ones.

“That was very much what we were interested in,” says Jonas. “Part of what was interesting about it was the pressure cooker of the human mind, and this one individual who feels the weight of the world, literally, on her shoulders, and how that affects everything and how it ripples through her whole life and how it affects not just her relationships, but that it's all sort of cyclical, because her crumbling marriage, or her struggle with a friend, that all relates back to the work at hand, which is save the world. And so these things are intrinsically linked. And we don't think about that, really, when we think of heroes, so it was an interesting way in to the material.”

Filmmaking itself involves very intense bouts of activity. Do they relate to being under that kind of pressure and trying to fit around the rest of life?

“I guess,” says Jeremy. “My wife's a teacher, sculpting minds, and responsible for human beings that are going to grow up and hopefully not become assholes. We're making entertainment for people like you to come home to after a hard day. When I was younger I used to be like, ‘Oh, I'm what I'm doing is the most important thing,’ but as I've gotten older, I think I've gotten more mature. I love my job. I think I have a lot of respect for what I do, and I know why I do it and its place in the world, but I also have that bigger picture thing going. I'm not saving lives the way so for me, I try not to let it make turn me into a monster, I think is what I'm trying to get at. It's like this: what we're doing here is supposed to be entertaining. And if it's not fun, why are we here? And why are we doing it?”

There's another big issue in the film, which plays into the real world under different ways, and that’s the whole question of raising a child in the world and how confident people can feel about that today.

“That's a great one,” says Jonas. “Jeremy and I are both parents. We both have two kids. I think Jonah and I would both agree that there's never a good time to bring kids into the world. And, you know, arguably, maybe we shouldn't, but I think kids represent hope. At least that's what I was trying to get at in this movie: the fact that they're willing, it says a lot. A person who is willing to have a child in these circumstances, that means that they believe that there’s future, It’s a glass is half full kind of thing, right?”

We go on to discuss the nature of the catastrophe in the film, and I mention that I was reminded of Kurt Vonnegut’s ice-nine. Jonas tells me that they took a while to figure out what their catastrophe would be, starting with the idea that the world’s water supply was polluted.

|

| Water, water, everywhere |

“There's a lot of science behind what we came up with, that's not in the movie, because it would bore you to tears,” he explains. “But this idea that our bodies suddenly reject water, I mean, technically, the idea that we researched was that our bodies were pulling apart the molecules of water and that the hydrogen was poisoning us. There's something about the paradox, though: this idea it's the very thing that we need that's killing us. Jeremy and I liked playing with gently playing with the metaphor of love, and love being this thing that that we seek and we need, and that feeds us, but also tears us apart.”

We see water in the film in all sorts of different contexts.

“What Jonas and I like to do is we like to take scientific, nerdy ideas, and then tear them down into things that are actionable and visual,” says Jeremy. “We knew we were making a lower budget film so the idea of like, ‘Well, what if water just dried up?’ – we're not going to be able to show that visually on screen, we don't have the budget to do something like that. So we wanted something that was, you know, budget friendly, manageable, but also something that we could make mundane.

“Look at the way that now, everyone just keeps masks in their pockets and hand sanitiser in their backpack, and other things that we just have, all these Covid related items in our lives now that we don't think anything of, right? So we went over what would those items be in this world where you're constantly probably dehydrated. And so we talked about how people would have their own water bottles, you'd probably mark them somehow so that way you could keep track of how much you're drinking.

“One of the things that you know is that your hands are going to be dry a lot, so there's little moments that we sprinkled throughout: our characters are constantly around moisturisers in the background. And I wanted like the idea of when she gets up in the morning and she breathes into this device, kind of the way somebody would step on a scale. Just ways that we could fit it into their day to day life without it having to hit us over the head.”

“For us as writers. It was an it was an exercise in storytelling,” says Jonas. “You know, the instinct is to have – you know the [film id= 14627]Jurassic Park[/film] animated video of how the mosquito took the took the blood from the dinosaurs? We came up with this fabulous idea and we talked to chemistry consultants and water scientists, and then it was a matter of like, ‘Okay, now we know all that, now throw that away. How would this manifest in a visual, physical and character way?’ Jeremy would have to pull me back many times when I when I would suggest other ways that we could tell the audience what's going on in the world. And it was push and pull between us. It's one of the things that we do well together.”

Set the way it is, it's a very budget friendly film, with just one location for most of the running time, but how did they go from there to making that location interesting visually?

“We picked that location because it's in my family,” says Jeremy. “It's been in my wife's family for 200 years, that old farm. I wanted to make sure that as this was essentially for actors, and mostly two actors talking through the relationship, I didn't want it to be like, five scenes in the same room. I wanted it to be as visual as possible, and I knew that the farm offered us those opportunities. I knew it offered us open spaces outside. The farm itself has depth, in a lot of the rooms. I knew I wanted to use the barn somehow. We had got to bring the river into it somehow, because of water being such a heavy thing and also it just looks gorgeous and picturesque and all that kind of stuff. So I think that made it easy because it didn't feel like we were just shooting a chamber piece in one location, because the farm itself offered so many so much variety.”

There are things going on in the film which aren’t immediately apparent at the outset. Jonas and Jeremy ask me when I caught on to that, and tell me that it was earlier than most people, but I point out that, as a critic, I don’t really watch films in the same way. We won’t go into spoilers here, but I asked them how they structured the plot so as not to give too much away too early, but to gently raise viewers’ suspicions.

|

| Ashgrove poster |

“That was that was the thing we probably were most conscious of in the editing process,” says Jeremy. “Where and how much do we get away early so people keep invested, knowing something else is going on? How are we going to play it out? So we kind of like made a note of like, let's have a couple little things. That way, if you miss one or two of them, another one's there. And they don't necessarily feel repeated. They're all different pieces of information and little weird things. So we made a conscious list of things we could do. It was about baking in enough of those things early on. And there is a bit of intrigue but without tipping our hat.”

“And then we tested it,” says Jonas. “We showed versions of the movie to test audiences, and we were really gauging, you know, at what point do you start to suspect a mystery here and does it hold your attention? And we would modulate the versions of the movie until we found what we think was ranked the best among our audiences. It really felt like we hit the sweet spot. And I don't know, I mean, you saw our last movie. It was maybe not the most...” he laughs. “I mean, there’s a lot of dick jokes in our last movie, not the most subtle of sci-fi comedies. And so I think this was a real exercise for both of us in restraint, and figuring out how much you could keep back and still hold an audience's attention.”

“We went into this film knowing we wanted it to be an exercise in acting and an exercise in playing with scenes and performance,” says Jeremy. “And so a lot of times, we would do multiple versions of scenes. We have a very loose version of a script that we work from, and then I talk to, usually, each of the actors on their own, and then we put it up on the screen and see what would happen. We start refining from there. But then other times I would go in and give one of them a curveball that would throw the other one that didn't know what was going on. It created this wonderful sense of unease where, you know, Jonas and Amanda have no choice but to be completely present, because it's never going to go quite the same way twice. And so it purposely put them on their toes. But it also allowed them to really respond to the moments authentically, so if there was something that felt like they could laugh or get frustrated, it allowed them to really just be and honour whatever they were feeling and going through without having to go ‘Well, no, that doesn't fit what we're doing.’ You know, because we were sculpting it as we went.”

With James Vs His Future Self, there were lots of different things happening in the storyline, there are lots of twists. Here the pace is very different. Was it a challenge, shifting into that gear?

“No, that was what made us excited about it,” says Jeremy. “On that drive, the one thing we said was that we want to do something that's different than anything we've done before, and work in a way that we haven't worked before. So that was by design. What we did with James was more narratively complex, but narratively complex in a different way, where it's more that things are weaved in and out and you have to make sure your things are set up a certain way, in order. It’s much more traditionally scripted. And, you know, Jonas and I, that's what we normally do, and we enjoy doing that. And we knew we could do that. But we were like, let's try something else.”

“We were very aware of the risk,” says Jonas. “There's a risk inherent there. The first half of the movie is has a bit more of a meditative energy. You're getting to know these characters, you're trying to figure out what's going on between them. So it's a more meditative, more thoughtful way of telling the story, and that's risky for two guys that have made successful careers writing five jokes per page. It was an exciting risk. Our whole motto from that first car ride right up until today on this movie was ‘no expectations’. Like, let's just try an experiment and play and see what happens, and if people love it, great. And if they don't, that's okay, too. But so far, it seems to be going pretty well as far as, you know, the world première at Glasgow, and a few more festivals to come.”

They’re about to announce their Canadian première, they tell me, and they have a US première coming up. They’re doing pretty well with s a small film where one of the rules, Jeremy explains, was that it’s okay to fail. They were not, he says, looking for any specific result: it was all about experimenting, discovering and trying to capture honest moments.

Jonas agrees. “Even our composer [Ian LeFeuvre], who's also a great songwriter, he pitched to Jeremy early on with ‘I want to score the movie, I want to write original songs and play these songs,’ and the movie is almost entirely mostly scored to his original songs. It's an unusual way to score a movie, but you know, it was an exciting, new opportunity for him to take that risk. And he wrote beautiful music for it.”

How long does it take to actually shoot when taking that approach?

“Oh, we shot this movie in ten days,” says Jeremy happily. “That's definitely the shortest shooter I've had for a feature, by least a week. But because, again, it was all very intimate scenes, we didn't have big location shifts. We went into it knowing that we wanted to keep the lighting simple so our DP didn't have to spend hours and hours lighting scenes and whatnot. We also shot the film chronologically. You know, normally you don't. If you have two scenes in the bedroom that don't take place back the back in the movie, you would shoot them back the back anyway. So every time we went into a new scene, we had to light that the first time, which is the wrong way to shoot a movie, for scheduling purposes. But because for the arc, I wanted to try to build with the actors, and knowing we wanted to keep a bit of a discovery method with the script, we just kind of set ourselves up to do that.

“We had always designed our budget and schedule around a 15 day shoot, knowing that if we needed to go back, when the editor found holes or whatever, we'd have five days to go back and reshoot. We didn't end up using any of them, because we were really happy with how it all panned out.”

The chronological approach was a big help for him as an actor, Jonas says.

“It's a lot more fun to track the characters’ journey in real time. I mean, a boring part of an actor's job is you have to chart out, you know, when the same day you're shooting, say, the first scene of the movie. and the third last scene of the movie, and your mindset is so different in your mental state and your motivation and your energy. It's amazing to shoot chronologically because you're just following the story. It's almost like play. And again, with Jeremy, the reason we did this was so that Jeremy could throw curveballs and we could modify and we could rewrite on the fly. It was an absolute joy.”

Both of them now have other projects in the works.

“ I have a movie that I shot I just shot in January, that's in post production right now,” says Jonas. “It's a sexy romantic comedy called The End Of Sex. And that'll be coming out later this year or early next year.”

“Yeah, and I shot a movie almost right after this,” says Jeremy. “A couple months later, I ended up going on a plane and shooting a movie in the Cayman Islands called Daniel’s Got To Die. That has been previously announced as, I think, Blue Iguana, but it's been retitled. So it's going to be coming out sometime this year."