|

| Christophe Cognet: 'I discovered the book of an Israeli writer, Leïb Rochman, À Pas aveugles de par le monde' Photo: l’atelier documentaire |

|

| Christophe Cognet with Anne-Katrin Titze on a film always being in the present: 'Hic et nunc in Latin. It’s very important for me. It’s the same in Alain Resnais’s film Nuit et Bruillard' |

A few clandestine photographs, taken by courageous prisoners in Dachau, Buchenwald, Dora, Ravensbrück, and Auschwitz-Birkenau are at the core of the documentary in which Cognet with the help of his cinematographer Céline Bozon, his team, experts, and translators at the respective memorial sites attempts to find out more about the individual circumstances. In reconstructing the angles of where and when the photographs were taken, an important path into the past opens up.

The life-size transparent prints of the images when placed at the original sites, have an uncanny, provocative and very bracing effect. Visitors to the concentration camp memorial sites walk by and for seconds the past and present in our eyes merge into a tinted timelessness of an always now.

From Paris on Bastille Day, Christophe Cognet joined me on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on From Where They Stood.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Happy 14th of July, I am glad we can talk about your remarkable film! It sheds so much light on the photographers. At the core is that we have the equality of the photographer and the photographed. Was this also for you the starting point?

It was very important for me to consider the physical things of the photography. Visual things, but physical things first. Then I discovered the book of an Israeli writer, Leïb Rochman, À pas aveugles de par le monde. In English it is Blind Steps On The World, but I think it’s not translated into English. These blind steps made me think of photography. You know, first I made a film about the paintings made in the camps, the sketches.

AKT: Your film from 2014, Parce que j'étais peintre?

CC: Yes. Then I thought it’s finished for me, the Shoah. But then I discovered this book by Leïb Rochman. We can make a drawing but we can make the drawing afterwards. To make the drawing we don’t have to be physically in front of the subject. It’s the opposite for photography. For photography you have to be physically in front of the subject, but it’s not necessary to see. This is why I wanted to do this film.

AKT: There are powerful moments in your film that express exactly that. One of the clandestine photographers in the camp clearly made the photograph with the body, not the eyes.

CC: Yes, like that, under the arm.

AKT: You start with the most physical remnants.

CC: Yes.

|

| Christophe Cognet: 'Claude Lanzmann said there is no image of the Shoah and if I see an image I destroy it' Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

CC: It’s in the camp of Birkenau, Auschwitz II in the area where the crematoria and the gas chambers were. When the corpses were burned, we have dust, ashes, and some bones. Big bones and some prisoners had to crush these. And after that the bones were thrown away in the pit. Over seventy years later we still have these bones. I wanted to make the connection with photography. Because for me photography is a physical trace of the subject. Chemically a photograph is some light going on the film. I wanted to connect it with these bones.

AKT: So the bones in the beginning are in Birkenau, not Dachau?

CC: It’s Birkenau in the area where in the end we see the pits, the graves.

AKT: Whenever I watch or rather rewatch Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, Four Sisters, or The Last of the Unjust, I feel that there is no time. No time has passed. What he talks about is here, now. We are always talking about the now. Time collapses in itself. What you do by having the photographs physically in the remnants of the camps is pointing to this. We are here. The past is never dead, to quote William Faulkner once again, it’s not even past. Is that what you were thinking?

CC: Yes, absolutely. And I learned the lesson that a film is now. It’s always here and now. Hic et nunc in Latin. It’s very important for me. It’s the same in Alain Resnais’s film Nuit et Bruillard.

AKT: Oh, yes.

CC: It’s to find in the place of the present the trace of the past. Photography to me is moving because the past and the present are next to each other. Before the film I did not know if it would work, this kind of thing.

AKT: You have a moment when tourists are posing under the Arbeit macht frei sign at the gate. People wearing vertically striped pants to go to a concentration camp? One woman, at first we think she wants to walk away, then she wants her picture taken. Anyway, it is such a different feeling than what we get when we see the tourists through the dispositifs of the photographs set up. You get the feeling of the past merging with the present.

|

| Christophe Cognet contemplated working with Shoah cinematographer Caroline Champetier on this film: '… but she was with another project' Photo: Anne-Katrin Titze |

AKT: It’s the very interesting in-between that only cinema can provide.

CC: Only cinema, yes.

AKT: Cinema can make us feel the uncanny, the ghosts, the return of what is still there. I was haunted by your film. The images of the women who were exposed to the horrible experiments in Ravensbrück - the photographs are so so very powerful. The kindness that is expressed as well. You explain that they got the nicest coats from their fellow prisoners because they had to go through the SS experiments of having their bones broken and legs shortened. The photographs are incredible. Can you tell me more about those?

CC: Yes, I discovered these images when I prepared the film. All the other images I knew before. They are the most emotional for me, because you see how they look themselves to make the photograph. They do their hair, they choose the light, make it like a little studio to take the pictures. It’s incredible. At the same time to have an image of them for eternity, because they think they are dying. The image they left is a unique image of them. It’s doubled in that image to show the wounds and them. When you see the pictures made by the American Army after the war of their legs, it’s horrific with the light on all the blood. With this image they made themselves we see their humanity. We see their elegance at the same time as their legs. It’s very moving and complex images.

CC: Oh, yes!

AKT: Also the photographs that show the relaxed positions of some of the prisoners. It is brought up in your film that some may use this to say it wasn’t so bad. I felt the opposite.

CC: You say it! What I understood little by little is to make a photograph of yourself in the camp it’s always an act of resistance. It’s human resistance, not political or military resistance, it’s moral resistance. It’s to see themselves like a human, not a machine or an animal. I think we see this in these pictures. The picture made by Rudolf Císar in Dachau went out of the camp and was seen by the resistance and family. So family can see that he’s doing fine. It’s a way to reassure the family. There is all this meaning in this photograph.

AKT: At the beginning of László Nemes’s Son of Saul, which leads us in fictionalized form into the camps, I thought I couldn’t take it. I couldn’t go in there with him. I talked to László a number of times and I think his film is very important. Entering this perspective, were you hesitant? How did it feel for you to make this film? Was it painful, was it a quest?

CC: It’s different, a documentary and a fiction. In a documentary we go in the real place of the crimes. In fiction we can invent. In documentary we can sublimate why we are here for the photograph to make an homage to the photographer. All my work is to try to have the visual perception of the prisoners. Not the perception of the Nazis, not the perception of the liberators. It was a very special moment for all the team. Something was stronger than us: we did it in a second state, the État second. After we left I slept for one month and something was in the stomach.

AKT: I liked very much how you were identifying your collaborators. From the crew to the translators at the memorial sites. In the end at the “staging” in Birkenau, although it isn’t really a staging, more a finding of the perspective for the crematorium, there is also a shoutout to Céline Bozon, your cinematographer. She is the sister of Serge Bozon?

CC: Yes.

AKT: I met Serge a number of times. Anyway, you name and place everything in your film and nothing is hidden. The sounds, the birds, all of this is now. You try to keep the fake away as much as possible, no?

AKT: I noticed that you thanked the great cinematographer Caroline Champetier, who worked with Claude Lanzmann. How was she involved?

CC: Before Céline we thought of them to shoot the film, but she was with another project. It was the first time with Céline Bozon and we became friends. Céline came from fiction films.

AKT: I saw you did a short in 2017 with Mathieu Amalric. What is it about?

CC: I can send you the link. It’s a short fiction film [Sept mille années], an adaptation of a poem by Nick Tosches, the New York writer who died about two years ago. He was a friend of Patti Smith. I tried to adapt his poem with Mathieu and with Françoise Lebrun, who was an actress in La Maman et la Putain [The Mother And The Whore], the famous film. It’s like an essay for me, this film.

AKT: So it is quite different from this subject matter. I also wanted to ask you about the controversy concerning the Birkenau photos.

CC: It’s an intellectual controversy the French like. Georges Didi-Huberman, the famous historian and philosopher, and Claude Lanzmann are the two counterpoints. In 2000 in Paris there was a big exhibition with photographs of the camps. In these photographs from Birkenau was the Shoah for the first time in France.

|

| Christophe Cognet: 'All my work is to try to have the visual perception of the prisoners. Not the perception of the Nazis, not the perception of the liberators' Photo: l’atelier documentaire |

AKT: I agree, that is not the role of the image.

CC: They can attest, but not prove it. It’s not the same thing. Didi-Huberman said the images can prove something.

AKT: You don’t go into that controversy with your film.

CC: I was then much younger, I mean not young physically but young in my research on the Shoah. We can’t talk about this subject without having read numerous books. I have worked on this 20 years and now I can tell a little.

AKT: The point of time for this film is now, when most of the remaining witnesses are dying. We have to move on from the oral accounts that were still possible. Now we have the bone fragments and the photographs. What does that shift mean for you? You must have thought about these crossroads while making the film.

|

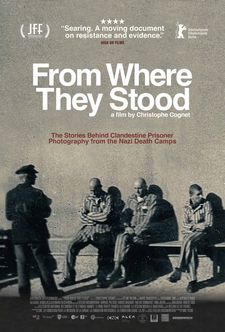

| From Where They Stood poster |

AKT: Physically.

CC: Yes, this is what I try. But I insist we can do this after the before.

AKT: I did feel it. I had just recently found out that an ancestor of mine was murdered in Dachau in 1943. He was there as a political prisoner from April 1942 and died at the age of 38. I was looking at the photographs and couldn’t help thinking is this him? Are these bones that share my DNA still scattered? It’s all very close and I think your film does marvels. So thank you for this.

CC: Thank you very much! And thank you for this conversation.

From Where They Stood opened at Film Forum in New York on July 15.

![Christophe Cognet on his short Sept mille années with Mathieu Amalric: 'I tried to adapt [t]his poem with Mathieu and with Françoise Lebrun, who was an actress in La Maman et la Putain, the famous film. It’s like an essay for me'](/images/newsite/Mathieu_Amalric_in_New_York_yFGSaiC_225.jpg)