|

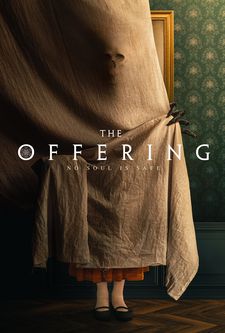

| The Offering |

A portrait of a troubled family facing more than one kind of crisis, Oliver Park’s The Offering mixes Jewish mysticism, horror, and the social difficulties which arise when a young Jewish man leaves the Hasidic community to take a gentile wife. He (Nick Blood) longs to reconcile with his father, Saul (Allan Corduner), but the situation is further complicated by his urgent need for money, which has him considering the potential value of the family home and the mortuary business beneath it. It’s his pregnant wife Claire (Emily Wiseman) who actually gets close to his father, as each of them strives to adapt to make room for the other – but when the body of a man with a dark secret is brought in to the mortuary, a threat emerges which changes everything.

Beautifully crafted performances, stunning set design and great attention to detail all round make this one of the standout horror films of the past year, and it will hit US cinemas and digital this Friday (13 January). Several months after I first saw it, when it screened at Fantastic Fest, I managed to catch up with Oliver to talk about how it was made, and I began by asking him how much of the excellent team was already on board when he joined the project.

|

| Oliver Park |

“I think if you were to speak to the creators, Hank Hoffman and Jonathan Yunger, they said they came up with the idea about seven years ago, so they've been working on this idea for from creation story up to the script for about seven years. But I came on about eight months before we started shooting. We did various forms of script reiterations working together – myself, the writer and Jonathan Yunger, and the other producers as well, to really dive into the script, to make it as authentic as we possibly could make it as scary as it possibly could.

“I remember when I pitched to come on board, one of the things I did was I told them one of my nightmares, because all my inspirations come from my dreams and my nightmares. So I pitched them this really scary nightmare that I had, and immediately the writer said ‘Do you have any more?’ And so he and I then worked with every scary idea I could bring to the table.

“The shoot was going to be in January, so we had about six to eight months to work as much on the scripts and get this as as fantastic as it could possibly be. So I came on late into the process, but I think I came on at a good time, because it gave him the ability to really iron out the story and the characters. And this is a story that, although I think it was Jonathan who came up with the idea to do a Jewish horror movie, Hank grew up working in a morgue. So that was his job, watching over the dead. So it also enabled him to really lean into the horror, through me just bringing as much to the table as I possibly could. It was a fantastic team.”

We’ve seen a wealth of Catholic-themed occult horror films over the years, but although there are a few very strong Jewish ones, that’s still an area which feels underexplored. Did that mean that he had more fresh material to work with?

“That's a good question,” he says. “Obviously, when talking about a Christian horror film, the first one that comes to mind is The Exorcist, obviously. And within that, they push the boundaries. And one of my earliest questions to the producers in the studio was, how far can we push the boundaries with this? So it was that that led us to the idea of a cracking mezuzah, and various things that use the Jewish culture, through horror. So we came up with our own version of the crucifix. There were things that were absolutely 100% off the table and there were things that we could play with. So then we took away our what we can and can't play with, and we tried to inject as much trauma, drama and horror into that as we possibly could.

“I'm sure when they made The Exorcist, the studio was pushing back on a lot of the things they did in that movie. I'm sure you'll get just as much pushback from any religion or any culture if you're aiming towards a certain culture for a story. But I think they were just probably wise enough to say, Ollie, there are some things that even we aren't willing to risk. And I think one of the best things with horror, I think you can really go to some dark places and you can explore some really dark themes. And I'm really glad that the producers were open to discussing what we could and couldn't do. I made their jaws drop a couple of times with some ideas that I thought might excite people in the wrong ways.

“Ultimately there's so much to explore. There really is so much untapped area within Judaism, within just the plot of horror. And this is away from the stories themselves. The stories themselves date back way, way, way before things like The Exorcist, even things like Frankenstein – it was inspired by the Golem, which is a Jewish story. So I think that there's a lot more to explore and I hope that many more Jewish horror movies start surfacing, and that we see people taking risks and trying things, maybe away from the occult.

“So Hank, the writer, he speaks several languages, and one of the things he wanted to do was ensure that the rituals in this were real. They were real when recorded, and we changed one word in the final edit, just to make sure that we didn't do anything too drastic, but the authenticity of both the horror and story and the characters and the culture, we all pushed as hard as we possibly could to ensure that was as close to genuinely real as possible.”

Because Claire is being gently inducted into Jewish culture during the first half of the film, there’s a guide for non-Jewish viewers, but what becomes apparent is that Saul has a lot of gaps in his knowledge too.

|

| The Offering |

“Absolutely. Yeah, I think that's great, because it ultimately asks questions so I think it leaves us asking questions as well. I think the idea of just someone coming on board and knowing everything – even the Kabbalist in the story, even he doesn't know everything. He knows some of the things but he doesn't know everything. So I think that's really important with a horror. Horror is the unknown, and as soon as you understand it and know it, it becomes combatable. So it was very important that, on any given level, a demon with the presence of someone like Abyzou, who is not the Jewish demon, she is a very old demon that crosses religions – for all we know, she is the original Lilith. No one knows, but there's various texts pointing to her throughout the ages. So it was important that something of this power was not fully understood.”

Balancing that is the wonderful characterisation in the film. We’re scared for these people because we feel close to them. How important was that human element?

“Absolutely paramount,” he says. “I believe within horror, scares come from character, through story and character and drama, and I think in the best horror films it's always an underlying trauma that's going on, where there is some kind of metaphor or theme that we as a society can see in the film. So, you know, within this, we've got a child, essentially, who left the community and this child like mentality comes back. He tries to do the right thing but he's just not there. Because he doesn't want to hurt his father. He's in difficult financial troubles. He's got a pregnant wife, he's worried about losing her. He's worried about losing himself, his father, his child. There's so many different angles of trauma within this film, and fear, that yes, you could remove the supernatural quality from the movie completely and you'd still have a terrifying drama about a son just wanting to reconnect with his family.

“Especially within the Hasidic community in the Jewish faith, I can't imagine what it must be like for someone to be told to leave their family, or leave their family when they're young because they don't fully understand what's going on, and not be welcomed back, which happens across the world in various cultures and faiths. It was one of the things we wanted to really raise the tension in this film. Through Heimish mainly, so the idea of ‘This guy left. I don't trust him. Why is he back?’ Well, maybe he's back because he genuinely does want to rekindle this family, so I believe, you know, there's angles for everyone - because I think we all understand various forms of what these characters are going through.”

He’s also an interesting character because despite his desire to reconnect with his family, he’s pulling away from the past, determined to live in the modern world. And in this situation, it’s actually ancient knowledge that he needs to survive.

“Yes, absolutely. Yes. And there was the importance of the fact that this is someone who left the faith and even forgot the language, so to speak. And at the very end, in order to fully overcome this demon and win and finish that prayer, he had to drop the book, he had to no longer read it, and he had to do it from memory. Fundamentally, that rise of the hero was so important to the story. So yes, all of those things are in there, as much as we possibly could in the timeframe we had, and keeping the pacing going, keeping the fear going.

“I think this could have very easily been a 90 minute drama. There was so much. When I first read the script it was 130 pages, which is what probably a three hour film if you're doing a horror film, but there was just so much there. Hopefully the film does very well, people love it, and they want more, because then we can explore more, we can go back, we can do prequels or sequels. Or we can certainly explore more within those characters, more within the community and just, yeah, dive even deeper with the lore. What these characters need to go through in order to combat something like Abyzou.”

|

| The Offering poster |

Despite having so much to get through, Oliver takes parts of the film slowly, both in terms of the drama and with individual, lingering shots. I compliment him on that, as I think it’s very effective and yet it’s something which a lot of directors are afraid to do.

“Thank you,” he says. “And you're completely right. I think that time and tension do go hand in hand. Pacing is very important for a horror movie, especially when you're working with a studio like Millennium who are used to action movies. I say used to – they can do anything – but you know, they primarily do action movies. But it certainly wasn't difficult to convince anyone.

“Obviously, with the short films that I've done beforehand, it was very easy to see that we can take our time here, we can slowly push in and let the audience feel it. And the producers in the studio saw that as well. We were working very closely together on the final cut. And the pace was very, very important, especially when there are arguments, and there are some fast paced moments. And I think they are complemented quite nicely with the slow moments where we, for example, go into the night-time sequences, or when someone's alone. I allow that space just to build.

“I think it's because mainly in horror, the audience wants to be scared, so I don't think you need to do much. Just stop the camera for a moment, or don't cut when the audience thinks you're going to cut - the audience move back in their seats. You don't even show them anything. That's the beauty of horror. I think the beauty of that in comedy would be having a stand up coming on stage and saying nothing, and the audience laughing. In horror, you buy your ticket, you already know you’re in for a fright, especially if you've seen the trailer and you know what kind of tone the movie is going to have, and then the rest is by simply just not giving the audience what they want, because the minute they know where it's going, it’s less scary.”.

Even when the camera is static, there’s a lot of story being told, because the production design is so rich, the sets so detailed. How involved was he in that side of the film?

“100%. Myself and the production designer Philip Murphy worked so well together, I adore him. My background is actually architecture. So I studied architecture and that’s what I worked as for many years, and myself and Philip came up with the idea in the design of how we were going to play things out. I'm not taking any credit for this, by the way, he is an absolute genius, as is the art director [Ivan Ranghelov], everyone there is. But I brought myself, the writer Hank and the producer, Jonathan, into every single level, so that we could ensure that authenticity and, like I said before, make sure that there are many layers to this.

“If you just pause the film, and you look at the apartment, in the opening scene – Yosille’s apartment – you can see the depth of where this character went, so that you believe maybe he actually did do what this film professes. Maybe he really did conjure a demon. You can see the various forms of languages, the hundreds of thousands of books that he had read, and all these spells. You find out what happened to his wife. You can see everything. And I think that's just as important as the characters – the spaces around them are just as important. So yes, there are hidden messages and there are extra layers of things to see within every single scene.

“If you look at Saul’s house, you can see the stories of how it was built, where it goes. Where Arthur actually walks along the corridor at night, quite early on in the film, he thinks he hears a noise and he walks towards the stairs. At one point, he stops at a corridor, and he looks down the corridor, and there are stairs going up even further. And again, I think it was small things like that that really added to the fact that this isn't a set – even though it was, you know. This is a home, and we wonder where those stairs go. We all either had stairs to the attic, when we were younger, or we've seen those movies where stairs go up to a dark door, and all of us feel that fear.

“So every single level, it was important to make sure we went into as much detail with the time we had, and ensure that we were hitting those notes the right way. Speaking of notes, then obviously comes the score on top of that. I worked heavily together with Chris [Raymond], and it was a dream come true. We created something that really set the tone of the film. And that also is one of the reasons why it feels pacey at some times and slow in others, because if you look back at the edit, they're actually quite fast, but the music is slowing it down. Or the reverse.”

We’re running short of time, but I can’t leave without asking him about Allan Corduner, whose performance is the heart of the film.

Oliver smiles. “Yes, well, I mean, he's a veteran. He's an absolute rock star, so of course he's amazing. It was an honour to work with someone like him, to be able to learn as much as I did from him, and all the cast. But he's an absolute veteran and how he can just switch up and he knows how to make people feel things without feeling anything, he’s just a brilliant, brilliant, fascinating actor who can just turn up and say, ‘Right, you know what's going on in this scene.’

“I like the fact that I can tell people I'm working with the magic trick of what’s going on. So for example, ‘In this scene, there is a man talking on camera, but you're not going to be looking at him because you're going to be looking at the fact that his shadow behind him moves while he's talking.’ This is something that it's lovely to actually communicate to the actor.

“So Allan and I would work very closely and I would say ‘At this point, I want the audience in the morgue scene specifically to be looking towards that dark corner. So you'll be in the scene but don't distract them.’ He knew exactly how to do that. He knew how to make sure the audience weren't being distracted by his movements too much. When he's looking over the dead body, when he's walking towards behind the curtain, he gives us the ability to look where we feel we need to, where the threat might be coming from. I think someone with his experience to move someone dramatically, to make us cry – he's not in the film that much and you know – spoilers – when bad things happen, some people who have seen the film have become very emotional because of his incredible ability.”