|

| Another Body |

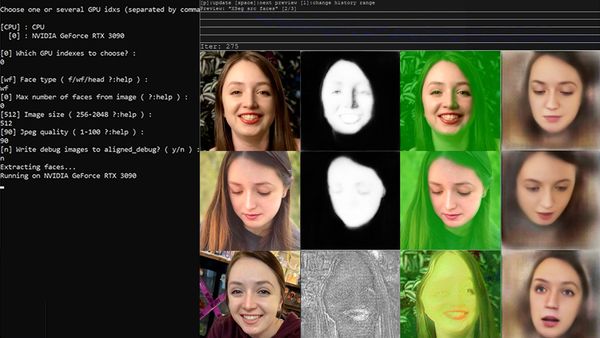

Imagine you found out that there were pornographic videos of you online. If you had never made any, your first reaction might be confusion. Welcome to the world of deepfakes, where your face could be attached to somebody else’s body – a phenomenon mostly talked about in relation to the political risks it poses, but which is most often used to harass women. Where it goes hand in hand with doxxing, it can put people at risk of both psychological and physical harm. That’s what happened to Taylor (not her real name), an engineering student who tells her story in documentary Another Body, reflecting on the distress it caused her and revealing, step by step, how she went about tracking down the person responsible.

The film was made by Reuben Hamlyn and Sophie Compton, and screened at SXSW 2023. Just after the festival I met up with Reuben to discuss it. He told me that he and Sophie kicked off the project by researching on 4chan, where a lot of key figures involved in producing revenge porn deepfakes congregated. At the suggestion of a specialist, they took single frames from videos and used an image search to track down the people who had been targeted. A side effect of the doxxing was that they could also go straight to the targets’ social media in some cases, and that’s how they made contact with Taylor.

“We consulted with a few survivors and the lawyer in the film, about the best way to approach it, and once we felt competent in how we were going to communicate with her, we reached out. Most of the message was just to be like, ‘Hey, we think you need to be aware of this, here are loads of resources that can help you, psychological or legal support. By the way, we are making a film, if you have any interest in sharing your story, reach out, and we'd love to have a conversation with you.’

“Taylor had known about the deepfakes. She found out a week or two before, but she wanted to speak, and once we talked about how we were trying to protect her identity and safeguard her and how it was going to be a survivor led approach to the story, offering her a little bit agency in the filmmaking process, she decided she wanted to share her story, because this could be a silver lining in that horrible situation and she could maybe affect some change. She agreed to do the film.”

I suggest that although it’s easy to focus on the technology and perceive this as a wholly new phenomenon, it’s really not a world away from the decades old phenomenon of scrawling graffiti on a toilet wall: ‘If you like sex call,’ followed by someone’s number.

“I think that this seems particularly dangerous to people because it's a pictorial representation of someone's body,” he says. “With the writing on the wall, you might have someone harass you over the phone, but you're not seeing yourself inserted into a hardcore sex scene, which feels like its own form of violation, because it’s not just a projection of the imagination of the person who's done this, but it it’s also a kind of reproduction of sexual violence. If you've been put into a sexual situation without your consent, it feels like it's an impression of that situation.

“I think that people have a very visceral response to that because of the way that we are naturally inclined to perceive images as reality. That being said, you know, photoshopping images has been around for a very long time. The capacity to do this with static images has been around for 20 years or so. Due to that, I think we are now more inclined to distrust static images because we know that it's very easy to make fake versions of them. We're still a little bit more trained to perceive video as reality. However, I do think that for a lot of those victims we spoke to, one of the biggest forms of harassment here is actually the idea that some may perceive this as real and your personal information is there, so in that sense there's a lot of crossover with the way that you're being doxxed by having a number on a bathroom wall, like in a truck stop somewhere.”

Does he think that people using this pornography believe it’s real?

“I think people will believe what they want to believe,” he says.. I think there was one person who'd commented on the video saying, ‘Oh, I think this might be a deepfake,’ but everyone else treated it as real. People that were like contacting her really assumed that she was publishing some pornography and soliciting, basically. I think because we spent a lot of time researching deepfakes, we were very familiar with them and we could tell they were a deepfake, but to the untrained eye, if you're not familiar with the technology and if you want to believe what you're looking at, it’s very easy to assume that these would be real. But that was in the early stages, and technology advances – I don't know if I would be able to detect a deepfake if it was done well now.”

I mention that there’s a page advertising deepfake porn which we see in the film, which links to lots of videos featuring celebrities and politicians. There’s a link to one featuring Greta Thunberg, and she would have been a child at the time. It would be illegal to make, distribute or watch that in the UK, even if the body involved belonged to an adult. I ask him how US laws handle that and he assures me that it would be criminal there too.

“A really horrible thing that survivors of deep fakes have been told to do is to try and determine if any images of them that were taken under the age of 18 were used to produce the video. The idea of going through your deepfake and frame by frame and being like, ‘Oh, was that photo taken from that holiday I went on with my family when I was like, 16?’” He shudders visibly. “It’s an impossible task and, you know, likely to re-victimise you if you're forced to scrutinise those images so closely.

“There are strange contradiction in the laws here. It's not illegal to do this to an adult because of the idea that it has to be your body being depicted. But that doesn't apply when it’s a child. Even when those laws were written, they were poorly considered about how technology was going to develop. There's not the same language when it comes to minors.”

As the film reveals, Taylor had an awful experience when trying to get help from the police. Did he and Sophie reach out to the police for comment?

“We did,” he says. ”We reached out to try and get any archival material from the police. We wanted to see if they had recordings of the phone calls that Taylor had made with the police, but the only one we were able to get was that original phone call. We got the police report, which was reflective of her like account in the sense that it seemed quite apathetic and lazy. We didn't ultimately put that in the film. We really wanted the film to be survivor led, we didn't want different people involved in the film.”

It was also about respecting Taylor’s wishes, he explains, as she didn’t want to have to deal with the police again for a final confrontation over the evidence she found. I note that a lot of what makes the film compelling is the intelligence and strength of character which she – and a friend whom she contacts partway through the film – demonstrate in acquiring that evidence.

“Oh my God, absolutely. When we started on the film we thought ‘Oh, this is going to be a 30 minute short.’ We didn't know that there would be more information out there. These people don't hide in plain sight. They hide in some of the weird corners of the internet. But you can go into those weird corners and find more information. The revelations that come out in the film are great for us as a filmmaker, and we're really glad that Taylor has been able to identify who the perpetrator is so they can protect themselves in their life. But as filmmakers, it's fantastic that the story ends up having so many twists and turns in it. It was really incredible, that doggedness. They were amazing contributors to have and it was really awe inspiring to work with them.”.

I was also really impressed by Taylor’s willingness to open up about her weaknesses in a way which most people are afraid to do, even anonymously.

“From a very early stage in the process there was some candour in regards to mental health,” he says. “However, I think the degree with which she confided with us and confided with the audience did grow over time, as there was some trust developing the relationship. There was a very close relationship all through quite a tumultuous time. We were in production during the pandemic so, you know, you don't have that much contact when you're outside of your normal social life. We were in regular contact and we became very close very quickly.

“I think she tried, as a matter of principle, to be open about her mental health. She understands that the only way to destigmatise it is to voice it. Although there was definitely some fear about the idea of being so open about what she goes through, she felt like it was the right thing to do.”

There’s a sort of coming of age moment – a very bleak one – when she and her friend become aware of what some of the men they thought of as friends really thought of them.

“Yeah. They were the two women out of 50 in that [engineering] programme. I think it was a circumstance where they felt like they had to just accept the sexism and misogyny in their environment. And I think over time, moving away from it, they were able to identify that it's not right that they have to be quiet and put up with it because that's their only option. I think part of that also comes from the fact that they’ve graduated from their undergrad. However, they’re entering into a very male dominated industry in which the boys might have grown up a little bit, but they haven't grown up that much, you know?

“There was an awareness that this was something they would have to put up with for a while, but at least the wool had been pulled from their eyes a little bit. Taylor was so young when this started, you know? She really matured over the production of the film, it's amazing to see how she's grown. She went from someone who felt like she was just out of childhood, when we started working with her, to a very independent, mature woman who's planning the next 10 years of her life with her lovely partner. I’m glad she has one really good man in her life. And it's amazing to see.”

I ask about the format of the film and he tells me that it was always their intention to use self-recording.

“There were two main reasons for that. One was that once we found out that Taylor had issues with mental health, we really didn't want to impose on her too much. We wanted her to have control of when she would tell her story and how she would tell it, rather than us just swarming on her with a production crew and invading her space in times of vulnerability. The second part of that was we thought it was thematically appropriate, as this is an online story and the images are created by scraping the content we put online. And so we thought that a video diary sort of format, which resembles the content you put online, it felt just like it was all tied together.

“We have this video at the end which celebrates women who are putting themselves online. We really don't want to put forward this thought that the solution to this is to erase your online presence. Online is one of the dominant forms of current society. And so we wanted to celebrate the way that people do exist online. It felt right to do it in this way. It’s a weird thing to say, but we became a slightly more attractive prospect as a film because we were more pandemic-proof, because we were already planning for a film that could be produced mostly virtually.”

Is he concerned about the risks of exposing an online community known for its vengefulness?

He nods. “We've had a session with some cybersecurity experts and we totally anticipate some form of harassment from people on 4chan. They're going to be angered by this or at least, even if they're not angered, we will just become the next available target. We've known this from the off and we're prepared for it. Yeah, I'd be surprised if nothing comes out of this, but we think that the story is so important that it’s worth taking those risks.”

He’s hoping that the film will reach legislators and inspire them to take action to tackle this type of harassment, he says.

“That's our plan. We want to change the narrative a bit. Most of the time when deepfakes crop up in the news, they really are talking about this perceived political threat to democracy and geopolitics I don’t know that there's going to be a nuclear war because there's going to be a deepfake of Vladimir Putin. I don't know. Like, maybe that would happen. I think that is very overblown. And they are completely eclipsing the real life impacts and effects today, which are the fact that women are being targeted. 90% of deepfakes online are non-consensual porn of women. So the most important thing is for the conversation to change.

“People need to be aware of this as an issue, and people need to understand that just because it's a virtual crime, it doesn't mean it doesn't have real life psychological impacts. We want to get that thought spread out in the culture and get people inspired to join us to change the laws here. We don't think there's going to be an easy solution. If it's just criminalised, that's probably not going to totally stymie the progression of this. I think there needs to be a multi-pronged approach from increasing the police training and resources for victims as well as legislation which makes it very difficult for online platforms to host deepfakes.

“We're not attacking pornography. If it's consensual pornography, that's great. But there are sites whose special purpose is to host non-consensual pornography of women. We think they should be shut down.”

Now that the film is out there, Reuben and Sophie are running a campaign called My Image, My Choice, aimed at doing just that. If you’d like to help, you can sign their petition.