You’re of Armenian descent, so I'm guessing that this was something of a passion project for you.

Sareen Hairabedian: Yes, exactly. I was born and raised in Jordan. So I'm part of the Armenian diaspora and I always knew about this region, Artsakh. I grew up singing songs about it and learning stories. So in a way, I always knew in the back of my mind that maybe one day I'd go there and do something. And then life took me to that place where I wanted to really go and tell the stories there.

How did you come to meet Vrej and his family?

|

| Sareen Hairabedian: 'I’m very dedicated to impact, and seeing how the film will help and will affect communities' |

Did the fact that you had a strong connection to Armenia yourself help you to form a bond with the family.

SH: Yes. I speak the language. The dialects differ a lot. But I was able to grasp the source of the words and really understand them and I think by the end of it all, we were really understanding each other. The cultural similarities really helped break so many barriers because you're already so much in line with how you feel about your identity as an Armenian. Also, when the war happened, the way I was empathising with what they were going through was so deep, and I was so affected by it myself that it just happened very naturally to want to continue filming with them.

Tell me a little bit about how and when you shot because I imagine that there was this sort of rumbling half-conflict impacting it, but also, presumably, Covid was interfering some of the time as well.

SH: At the beginning, when there was no war, I had plans to go every three months and to continue following him over a very specific period of time. But then when the war happened, in 2020, there was an urgency. When, in September, the war happened, I knew I had to be there. Obviously, not in Artsakh, but I wanted to be with Vrej. He was displaced within Armenia and I wanted to be with them and see the war from their perspective, see what's happening to them and how they are reacting to this conflict. And Covid was tough. Flying was tough. I remember I was one of the few who was flying to Armenia - I got to the airport and it was empty. But with the war, I think Covid became secondary, with people just wanting to stay close to each other. Especially with the family, there was zero distancing, none of that existed. And I actually did have Covid there and the family did. And it happened again. It was very risky but at the same time, I had a mission, and I just had to be there.

It must have been quite stressful for you when you weren't there because you're watching this family and the children go up partially from a distance. You must have been quite worried about them in between the shooting periods.

SH: Very worried. We had created such a strong relationship and a lot of trust between us. So they were like family. So whether it was that we heard news of another shooting on the borders or once the blockade happened - where they were blockaded for nine months - we were in touch regularly. At one point, I was not able to be there. I remember we were in the editing room and I called them, and Vrej’s voice had already thickened, he was hitting puberty. I was like, ‘Oh my God, in my editing room, he’s still a child, then when I call them he is already growing up’. I couldn't go and be with them because of the blockade. So a lot of it was a balance. Also not being able to access the region eventually - how do you tell a story when you can’t be there any more?

How happy were the authorities for you to go and film their “soldier kindergarten”, as one of the troops terms it? It’s a strong part of the film, this idea that the children are inheriting the expectation that they will go off and defend their land.

SH: I think it was years and years of them knowing my intentions of really closely telling the story of these kids, by having that kind of trust. We would sit in the teachers’ room and discuss what these kids are going through and why this is happening. So, I was very much engaged with them and in conversation with them when we weren’t filming. I think they were proud but they were also hopeless like, it’s unfortunate we’re doing this but there’s nothing else we can do.

One of the things that your film brings home is the uncertainty of war and the knock-on effect that has on families. People almost can't live their lives, because they're not sure what's going to happen tomorrow.

SH: Exactly. I think that is the general atmosphere there. They used to say, “We live in a cage”. As much as you try to be happy and make your cage beautiful, whether it's your garden, it's your home, it's your life in the village, at the end of the day, they know that there's something larger that is out of their control that is limiting them. It's not as easy for these children to really dream and follow their dreams, because of the status of their lands. And if you talk to every parent all they wish for is that their children grow up under a peaceful sky. This is their saying, and it is something that follows every other sentence. “Let's grow up under a peaceful sky.”

|

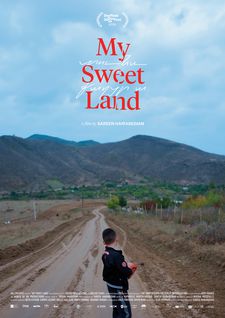

| My Sweet Land poster |

SH: They're in Armenia, very close to the village that they were in when they were displaced. They are trying to rebuild. The father is working, the mother is working. Obviously, they have different jobs than they had. I mean, the dad was the headmaster of the school back in his village and I think now he’s working with a shoe company helping in production. So really, you change roles, you change everything. Their main goal is, “We need to do the best to give these kids an education”. They were like that back in Artsakh and they are like that in Armenia because they believe education will be a way to freedom for these kids.

You've invested an awful lot of time in this film, for obvious reasons. And it lays out the situation very clearly. What's next for you going forward? Do you think you'll still be drawn to telling these documentary stories?

SH: I've dedicated six years of my life to this and they’ve become like family and documentary has just become a big part of my life. I don't see myself not working on another one, and another one, and another one. So I just feel that the work continues for me, and especially not just to make the film and let it live on its own. I’m very dedicated to impact, and seeing how the film will help and will affect communities. I also want to bring it back to Armenia and allow it to be a tool for healing in a way, working with nonprofits and organisations that are working with children, to help them find ways to process the trauma that they've gone through during the war.

For more information about the film visit mysweetlandfilm.com