|

| The Queen Of My Dreams |

Brought together by the funeral of the husband and father they both loved, a Pakistani mother and her Canadian daughter connect through their shared love of Bollywood romances and discover that they have more in common than they realised. Fawzia Mirza’s The Queen Of My Dreams is one of the biggest festival hits of the past year, playing at Toronto, London, Leeds, SXSW, BFI Flare and Frameline, among others, and now it’s getting a UK-wide cinema release. I was delighted to get the chance to chat with the director and to ask her about the process of bringing it to the screen, starting with the short of the same name that she made 12 years ago.

“I made a short film called The Queen Of My Dreams in 2012,” she explains. “I made that before I was a filmmaker, so I didn't really know what I was doing, but also I didn't make it knowing it would be a film. I had shot a bunch of footage. I was actor at the time, so I was thinking I would make a art installation, a live performance piece. And then it was a friend of mine named Ryan who said to me, ‘I think you can make this a movie,’ and helped me turn it into a three minute short film. I was in the short film. It was very personal. There's voiceover. There's a little bit of imagery from a scene in the film.

|

| The Queen Of My Dreams |

“We also, myself and another actor, we do drag, and we see us getting into the drag, and it's basically like me becoming the character Sharmila Tagore plays in the film [Aradhana]. And then this other actor, her drag was becoming the man played by Rajesh Khana. And then we were recreating, photographically, four scenes in the film. And so in many ways, the short was a bit of a reclamation of this song, these stories, this sort of love story, but told through a queer lens. And it was deeply cathartic.

I developed a one person show with a company in Chicago, and again, I was an actor, so I wanted to do the big one person show. And it was a very personal story. I portrayed myself, my mother, and Sharmila Tagore at different points in the play, and it was very personal storytelling journey. And it wasn't until about 2017, when I had been writing more films, that I made a feature film that I wrote, directed, and starred in called Signature Move. And so by 2017, it was like, ‘Oh, this project that I've been working on – maybe there's a screenplay in this. So that's when I really dug in and began to see how you would make that.

“It was a circuitous journey. I mean, making a movie is always a miracle. But that journey, I'd say, was circuitous because I wasn't a director yet. I wasn't a filmmaker yet. I wasn't making movies intrinsically yet. I had to find myself before I could find a path to making this film.”

I tell her that I liked her work in Signature Move, and that having talked to Jennifer Reeder a few times, it's interesting to meet the other half of that particular team. There’s a lot of cross cultural stuff going on in that film, and it feels like we're at a moment where we're starting to hear more voices of filmmakers from cross cultural backgrounds. To what extent has that been a factor for her in choosing to tell this particular story now?

“I think, you know, we all have stories we feel like we have to tell, whether it's a filmmaker or someone who's sitting around a dinner table, and we always love to tell a story to new people at that dinner table,” she says. “And so this project has just been with me. My work, probably unintentionally and intentionally, has centred queer, Muslim, brown people because there just weren't any in mainstream cinema that I had seen, or even in indie spaces. It was still so rare. And so my work really began as writing and creating out of necessity, not just for myself, for roles as an actor, but also, you know, how are you supposed to believe that you deserve to live and that your life has worth, that your story matters, if you don't see it represented anywhere? So I kind of backed into centring my communities and these voices. And so I guess it didn't feel like it was much of a choice that this would be my first feature to direct. It just sort of was going to be.”

|

| The Queen Of My Dreams |

There's a huge amount going on in the film, I observe, but one thing that interests me about it is the way that it ties today's struggles around both identity and sexuality with the mother’s struggles in the past, creating awareness that the same struggle, to an extent, has been going on for generations.

“Yeah,” she says. “I mean, I know that we live at a time that feels unprecedented in so many ways, or that we as people feel like we are so different and unique – and we are – but also we're not that dissimilar to people who came before us, when we really think about what drives us, what hurts us, what motivates us. The rules have changed and the technology and some of the systems have changed, but we still have these reactions and feelings and emotional landscapes that are similar to generations ago. That's always been of interest to me.

“I really believe that in order to understand who you are, you can't look at just the confines and borders of your own body. You have to look beyond. You have to look at those that came before you, and you also have to look at the world and the environment. I mean, the film touches very much on this idea of the wound that we carry is sometimes connected to a deeper wound. I'd say in the case of the grandmother, or maybe all three of the generations portrayed in the film, there's a wound connected to what the colonisers did to India and the wound of Partition and the wound of the land. So these intergenerational stories, I think, are so key to understanding who we are.”

That seems like a central theme of the film as well: coming of age and realising that one’s parents are also people and have gone through similar struggles.

“One hundred percent,” she says. “I mean, there's no way for us to know what someone else's life was or is. That is true of our neighbours and communities around the world, but also of our parents. We don't really know what it was like for them. They only tell us so much about their stories and their lives and their struggles. And so in some ways, I think The Queen Of My Dreams is also a bit of a fantasy. It's a re-enactment of what two people falling in love in 1969 Pakistan, what their life might have been like and how might have impacted the generation that came after.”

There are also incredible colours and bright Sixties costumes.

“You know, colour was really important to me. I'm inspired by Bollywood. I'm inspired by the motherland. And I think even when we are in grief, the colour of the world doesn't change. I think far too often when people are telling stories of another country or over there” – she gestures – “they tend to desaturate. I think sometimes desaturation is seen as more cinematic. And for me, colour is really important. Even when things are hard, even when things are tough, even when there is grief, the colour of the world just is and exists.

|

| The Queen Of My Dreams |

“I am deeply, as I said, influenced by Bollywood and those worlds. No matter what is happening, whether it's the love story, the grief story, the horror, the ghost story... You know, what I love about Bollywood, and I really intentionally use the term Bollywood, there's like, five genres in one, and I love that. No matter what genre you're in at the moment, though, the world has colour in it. And I'm inspired by that.

“I think Bollywood is very queer in that way as well. It's always more than one thing, just like queer people are. It's five things in one. Even the connection to this big, expansive love, to dreaming, to aspirational endings for life, for the singing, the dancing, the music, the wardrobe. What I love about classic Bollywood Indian cinema is the way masculinity is represented. Masculinity and femininity, and men's roles and women’s. Sure there's some gendering, but also there's a femininity in men that is, I think, aspirational. And so I also think that there is something about how do we become who we are? You know, we have to look to the past to understand ourselves, but the past isn't backwards. We have to glean truths from how we got here in order to better move forward.”

Regarding gender, a lot of films – or artworks more generally – suggest that there's one true way to manifest a particular gender, but here the two central characters have very different approaches to their gender. The film seems to be arguing that both of those things are valid ways for them to express themselves, and that the goal is simply for them to find ways of being themselves and being accepted.

“Yeah. You know, I love thinking about how external representation is one thing, and internal presentation or representation is another. I often think that if you were to take, you know, my mother, who wears hijab and wears a Pakistani salwar kameez every day, and then me, who, you know, I have big glasses and short, tight silver hair, and am often wearing a suit jacket and a button shirt – our external representation is one thing, but internally, our emotional landscape is quite similar. I think that has impacted me a lot in the work I do and who I am and also in understanding where we come from.

“The idea of gender being one thing feels so narrow and so small and so limiting and is not a reflection of where we come from. I think that is also a reflection, if we think about it, of Indian culture. I say Indian, using the sort of pre-colonised terms of the subconscious, but pre-colonisation, you know, on the subcontinent, the representation of people and community and gender is so vast and so expansive. And I just think we want more of that. We need more of that.”

|

| The Queen Of My Dreams |

There are a lot of very chaotic scenes in the film with multiple things happening at once. How did she keep it all as controlled as she did?

“You know, I'd like to say that all of it was conceived before, in pre production and on the page, but the beauty of making a movie is discovery and being open to discovery. I had great producers on the movie. My wife, Andria Wilson Mirza, Jason Levangie and Marc Tetreault out of Nova Scotia, and Damon D’Oliveira, who were on board for production. They were as committed as I was.

“There were certain non-negotiables, like we had to film in Pakistan. We wanted to bring some of our team from Canada, but then we really wanted to lean into the incredible artisans in Pakistan. So, you know, we were always striking a balance. Finding a great DP like Matt Irwin, who has such extensive knowledge as a cinematographer, meant that the lighting was going to be exquisite no matter where were. He could bring that knowledge that would travel with us. Or, you know, production designer Michael Pierson, who was able to work with both the teams in Nova Scotia and Pakistan in such an intimate way, as a true collaborator.

“That level of collaboration across the time periods, across both countries, with our producing team, also in Pakistan, that was essential, because this film is what it is because of those layers. It's because of the layers of music, of wardrobe, of production design, of place, the authenticity of place that is evoked in Nova Scotia and Pakistan. And then our editor, Simone Smith, you know, you get all of this great stuff and then you're like, ‘Now what do we do with it?’ We found some remarkable pieces and storytelling devices in the edit. I think editing is rewriting, and Simone was willing to try everything with me. The film wouldn't be the film without this.

“I was looking to rewrite the opening of the film from what was on the page, and I wanted some more connective tissue in the film. So I went back to the short film. I was like, ‘What was it about that short film that evoked something so strong in me that it changed my life?’ I already knew I was going to be using the footage from the original film in certain ways, but going back to the short made me feel like I needed to evoke memory right away in the film.

|

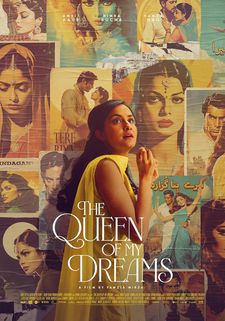

| The Queen Of My Dreams poster |

“That was what led to the opening scene as it is, which is both of the mother in a scene that we kind of connect to as being from the 1980s in Canada, plus that juxtaposed against the figure of Sharmila Tagore from this iconic moment in the train where she's looking at us from the film Aradhana, the movie within the movie. I decided to use some of that footage as connective tissue as well, throughout the film. Now I can't imagine the movie any other way.”

Finally, we discuss the film’s festival reception.

“What a blessing!” she says. “You know, a movie is a miracle. And my work is not just for me. It's not about it living in a vacuum or me processing alone. My work is very much about the audience, and I think about the audience and how the audience will receive the work in a movie theatre or at home watching it – I hope not on your laptop, but I know on your laptop.” She laughs. “And, like, thinking about the layers of joy, of comedy, of grief. I want us to feel that together. And so my work is about and for us. And so the fact that it's been received as it has is – you know, maybe it's a cliché to say it's a dream, but it is. But also, it's what I want my work to do. I want it to connect with audiences, more than anything.”

The Queen Of My Dreams opens in UK cinemas on Friday 13 September.