|

| Bing as Apollo with Naomi Watts as Iris in David Siegel and Scott McGehee’s wondrous and sage adaptation of Sigrid Nunez’s National Book Award winning novel The Friend |

In the first instalment with novelist Sigrid Nunez, we start out discussing the costume design (by Bina Daigeler) for Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore's outfits in Pedro Almodóvar’s enlightened The Room Next Door (Golden Lion winner at the Venice International Film Festival and Centerpiece Gala selection of the 62nd New York Film Festival, based on the Nunez novel What Are You Going Through) and the clothes (by Stacey Battat) for Naomi Watts (plus the cast of Bill Murray, Ann Dowd, Sarah Pidgeon, Carla Gugino, Constance Wu, Noma Dumezweni, Felix Solis, and Owen Teague) in David Siegel and Scott McGehee’s wondrous and sage adaptation of her National Book Award winning novel The Friend (a highlight in the Spotlight programme of New York Film Festival).

|

| Sigrid Nunez with Anne-Katrin Titze on Jean Cocteau’s Beauty And The Beast: “You know there's something about a man-sized cat.” |

Bing, the Harlequin Great Dane who steals the show as Apollo in The Friend (Fido award longlisted), leads us to the fairy tales of Sigrid’s childhood, the influence of Jean Cocteau’s Beauty And The Beast, Hans Christian Andersen’s The Tinderbox, Rapunzel, and the Brothers Grimm. Susan Sontag’s Cyd Charisse anecdote from her book Sempre Susan - A Memoir Of Susan Sontag, Rainer Maria Rilke, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Michel Houellebecq, Heinrich von Kleist, Jacques Demy’s Donkey Skin, Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone Of Interest, Jessica Hausner’s Amour Fou, and Greta Garbo’s reaction to the Beast turning into Jean Marais also came up.

From New York City, Sigrid Nunez joined me on Zoom for an in-depth conversation on the film adaptations of two of her novels, The Friend and What Are You Going Through.

Anne-Katrin Titze: Today is the last day of the New York Film Festival. Did you have a good New York Film Festival?

Sigrid Nunez: I did. It was quite wonderful.

AKT: The best ever, I imagine?

SN: Yes, for me. The best ever.

AKT: The two films based on your work are clearly highlights this year and really wonderful in how different they are. Were you surprised by how different these two films are?

SN: I guess I'm not. I'm not really surprised because I had seen the work of all the filmmakers before. But it's interesting what you say, because anyone who read those two books and didn't know who wrote them would be able to tell they were written by the same author. But watching these two movies, you wouldn't be able to tell that they were taken from books by the same author.

AKT: You could guess, but you wouldn't be sure. That's true.

SN: Yes, I mean they're different enough from each other that I don't think you would associate. If you knew both of these movies are based on novels, I don't think that someone who saw the movies would say that it was the same author.

|

| Beauty (Josette Day) and the Beast (Jean Marais) in Jean Cocteau’s Beauty And The Beast |

AKT: And it might have something to do with what I talked to you about when we met at Lincoln Center, namely the costumes.

SN: Yes. I love the costumes in both movies and with the Almodóvar, obviously, they're much more important for the actual visual aspect of the film, because he wanted that to be so intense, whereas in The Friend they just wanted things to look natural the way people would dress. Whereas with Almodóvar, I think it's part of the aesthetic to have those vibrant colours in the clothing.

AKT: Also the two women impress each other with their clothing choices. There's a bit of very interesting peacocking going on in the Almodóvar film. They show off their garments for their director and for each other.

SN: I can see that, I can see that. Yes, and that is not a part of The Friend at all.

AKT: No, she doesn't dress for Bing, who is Apollo, the Great Dane in the film. He cares about one T-shirt and one T-shirt only that belonged to Bill Murray’s character.

SN: One T-shirt, yes, yes.

AKT: I would love to talk a bit about fairy tales in connection to both movies and your work. The epigraph for The Friend has a quote from the tale The Tinderbox that you bracket between two quotes about writing and novels. In the middle there is this quote from Hans Christian Andersen about the dog. I loved how David [Siegel] and Scott [McGehee] took that quote and made it into a dinner conversation for the movie!

SN: Me, too. I love that, too, which is not in the book, and I was very happy with that as well.

|

| Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore in Pedro Almodóvar’s The Room Next Door |

AKT: I thought it was a fascinating solution and they had me hooked at that moment. But fairy tales do play a big role in your novel, The Friend, as well, especially Rapunzel.

SN: I don't remember. You know, it's so long ago that I wrote the book. Which was the Rapunzel reference?

AKT: About blindness and her making the Prince see again.

SN: Yes, her tears. Yes, but I don't remember the context in The Friend. But yes, yes, that's extraordinary, it's just extraordinary that when he climbs up her hair, and then the witch scratches his eyes, and then he tumbles down, and then she throws Rapunzel out too. And then they wander for a very long time, and then find each other. And then, when she weeps, her tears cure his blindness.

Yeah, I'm so struck by that, because that fairy tale, like many fairy tales, though it has a happy ending, as it were, is so full of cruelty. And now I remember that the narrator has some thoughts about the witch. Because, as she says, she took care of Rapunzel, she was good to Rapunzel. She protected her, and then she felt totally betrayed. And I think that that's something you don't usually think about, that nobody's going to take the witch's side in that fairy tale. But I think when I thought about it as an adult I did feel empathy for her, for that betrayal and that loss, because then she loses her. Her daughter.

AKT: Yeah. She's a protector as well.

SN: Protector against men.

AKT: Yes, against the Prince too. And then she sends her out into the wilderness, and there she is, giving birth to twins. What a story! Your narrator in The Friend says that fairy tales were her favourite childhood reading. Were they a favourite childhood reading for you?

|

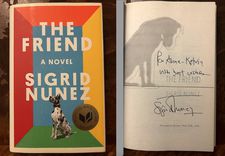

| The Friend inscribed by Sigrid Nunez to Anne-Katrin Titze Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

SN: Absolutely. You know, when I answer the question of, why did you become a writer, or what made you be a writer, it all goes back to fairy tales. Now, my mother was German and so the earliest reading, as a child when I was being read to by my mother, were fairy tales, Grimms’ Fairy Tales. And I was completely hooked on these. So once I started to be able to read myself, that's what I went for.

I would go to the children's library and take out the Red Book Of Fairy Tales, the Blue Book Of Fairy Tales, the Green Book Of Fairy Tales, Grimm, Anderson, Norse Sagas, and then mythology, which are their own kind of fairy tale, and that was it. I was steeped in that, and from there I learned what a treat it was to use your imagination, because when you're a child, children don't write auto fiction.

AKT: No, that’s true.

SN: And they usually write some version of a fairy tale. They make up a little tale. They don't write about realist stories about friendship and marriage and family. So I think, for most writers, rather the first things that they write are like fairy tales, and then they never get old. They always work. Even though they're short they're so full of things. Ideas of all kinds. And they're so full of beauty. They're beautiful. They're always beautiful. And they don't psychologise, which I think is really really important. There's no real psychology. There's no explanation for why this person grew up to be an evil sister, and this was a good sister.

AKT: It's through action.

SN: Yes, yes.

AKT: Actions and objects.

SN: Actions and objects and nature.

AKT: Yes!

|

| Catherine Deneuve and Jean Marais in Jacques Demy’s Donkey Skin |

SN: And also, I think, very, very important, metamorphosis. That was also something that was very meaningful to me as a child. The idea that you could turn into an animal. An animal, or a tree could talk, or just all of these things that I just thought were wonderful.

AKT: I have to say one thing before I forget. When you mentioned auto fiction, I had to laugh in The Friend when the first book that Apollo eats is a Knausgaard!

SN: Now one person said to me, a woman in an audience, she said: Was that a statement against Knausgaard? And I said, well, no, I wanted a big book that you would know how big and strong his jaws were. To think that he could do that, and also because of the timing. It was a book that she would likely have been reading at that time. And then I thought maybe it was just envy. Because at that time Knausgaard was having this extraordinary international success. But really it was mostly about, you know, I wanted to show how strong those jaws were.

AKT: Fabulous. So it is one of the volumes of My Struggle, I suppose. Or is it already The Morning Star?

SN: It's one of the volumes of My Struggle, yes.

AKT: Another point that I loved so much - I mean they didn't make it Knausgaard in the film - but a moment when I laughed out loud was the first time we discover Apollo’s love for the written word is with Rilke

SN: Yes.

AKT: It took me so long before I got it! I didn't put it together that, of course, Apollo and Rilke!

SN: Yes, exactly. Exactly.

|

| Sigrid Nunez at the New York Film Festival Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

AKT: Even though it took me forever to put those two together [Rilke’s Archaic Torso of Apollo ends with the appeal, “you must change your life”], I just loved the fact that this dog loves Rilke so much.

SN: Yes, and Rilke has also written all these wonderful animal poems.

AKT: The Flamingos I love. And The Panther, of course.

SN: The Panther, yeah.

AKT: I have to quote you back to you, because this is one of the sentences that probably struck me the most in your novel. “I believe the intensity of the pity you feel for an animal has to do with how it evokes pity for yourself.”

SN: Hmm.

AKT: That's at the core of the book.

SN: Maybe that page of what you read from, that was probably the hardest thing for me to write. Meaning it took the most effort to get it into the right words, because I knew what my thought was. But it was very hard to say. The problem is that when the animal is suffering, it can't tell you what's wrong, or whether it would rather you just let it die instead of trying to keep it alive. That’s very hard for the animal's owner because they don't know what to do. Then there's the story about the duck, the tortured duck that Robert Graves remembered as the most awful memory when he saw this in World War One. I mean, he saw terrible things, and I just thought, well, when you can't communicate except by crying and making little peeping noises then you are a little bit like that.

That helpless animal, not being able to speak, is really a condition of great helplessness. And of course you don't know that when you're little when you're a baby. But I think you must remember it. That's that you're completely innocent and completely helpless, and all you can do is try to make these cries. And we all have been there. So I thought that, yeah, so that's the connection that I made, and it was very hard to articulate. But I am happy in the end with how I was able to describe that.

|

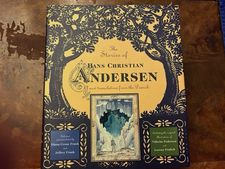

| The Stories Of Hans Christian Andersen, collection Anne-Katrin Titze Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

AKT: It's extremely profound. I became a wildlife rehabilitator because I saw injured ducks and swans in the park here in the city and I wanted to help. I felt so helpless. And they said, you can't help. You're not allowed to help.

SN: Not allowed to!

AKT: I asked what do I have to do to help to disentangle them from fishing line? And so I was told to become a Wildlife Rehabilitator, which I did.

SN: Wonderful, congratulations!

AKT: Thank you. This point about animals is something relevant in fiction and in films also. I think you can split filmmakers into those who exploit our feelings about animals, exploit the empathy, and those who don't, and sometimes at the start of a film, I wonder, can I trust them?

SN: I'm not sure what you mean by exploit. What I see is a couple of things. One thing is a kind of use of sentimentality. You get a very cliched sentimental attitude towards the animals, and the animals don't really have their individual lives so much as it's the humans’ love for the animal that makes the animal valuable. It's not like the animal has a value in its life, which is why we're so different with dogs than we are with the cattle that we turn into steaks. But I think the other thing is that, you know, Bill Berloni, who had done the training for Bing, we were talking before I'd seen the film.

AKT: I read The New Yorker article about him, which is great.

SN: Wonderful! We were talking. He had seen the film. I hadn't. It was right before Telluride, and he was talking about how the wonderful thing about the movie and being Apollo is that in these other dog movies like Lassie and Rin Tin Tin and a lot of these movies, the animal is a kind of hero, or does some spectacular thing, like the Black Stallion, for example, which is a movie that I love, wins the race. But there's not enough of just where the animal is a character, and you don't give it a human voice or a human outfit or human ideas. That's what I think you don't see. You don't see a lot of, you know. I'm not sure about what you mean, how exactly they exploit our feelings.

|

| Pedro Almodóvar holding up What are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

AKT: Exploiting on the most basic level in the sense of signaling that someone is a bad character, for instance. Look, he kills the hero's dog! The dog is a mere prop. These plot device animal figures aren’t really about the animal. You sometimes simply have to see that somebody has a dog or a cat in a movie, and you know it's only there to be sacrificed.

SN: Exactly, exactly, exactly.

AKT: Writing about films, those I try to stay away from. Another fairy tale that is about metamorphosis, the ultimate metamorphosis, one that is mentioned a few times, I think in both movie and your novel, is Beauty And The Beast.

SN: Oh, excellent! Yes, I think that was one of the most magical literary experiences I ever had. Reading that story as a kid. And then the Cocteau film. I guess at the time that I saw that, I might have been just out of college. I've seen it many times since, but the first time I'm pretty sure it was on television. There used to be a film series on public television of great films. And it was so unlike any other movie I'd ever seen. It was like the first time I saw Citizen Kane or Woman In The Dunes.

Or, you know, just all these movies that were so different from the Hollywood movies and the Disney movies that I'd grown up with, and that I thought these are movies. It was like my introduction to foreign films. Not that Citizen Kane is a foreign film, but you know. It was a special TV series, and they were almost all foreign films. So I just thought that Cocteau was utterly magic. And then, many, many years later hearing that Greta Garbo in the audience saw this incredibly handsome actor [Jean Marais] and said: “Give me back my beautiful Beast!” That just seemed, I thought, yes, that's the way I would feel. You know there's something about a man-sized cat.

AKT: Do you know Jacques Demy’s Peau D’Âne, Donkey Skin?

SN: No, I don't. I know the book. But I've never seen it. Is there a movie as well?

AKT: It's a movie from 1970.

SN: Oh, that's right. No, I've never seen it. I mean, I know the book. This is based on the Balzac?

AKT: Perrault. Jean Marais [both the Beast and the Gaston character in Cocteau’s Beauty And The Beast] plays the king, the father of Catherine Deneuve, who is the heroine.

|

| Christian Friedel and Sandra Hüller in Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone Of Interest |

SN: Of course, of course, I have not seen that movie, but I would love to see it.

AKT: His throne is a gigantic cat, that’s why I thought of it. He has a cape that makes him look like a peacock.

SN: I have to see it!

AKT: It's fantastic. It's one of my favourites. That line in The Friend about Apollo turning into Walter …

SN: Yes. And then that thought comes to her, you know, in the book it's because she's talking to Wife Number One on Skype and she says, well, I can't get rid of him, I can't. It's not his fault that he's old. No, I can't find him another home, etc. And she's obviously very emotional. And Wife One says, wait, who are we talking about here? Because it seems to her she's talking about Walter. He couldn't help that. So sometime later she has that thought. Is this the mystery at the heart of it? That if I think I couldn't save him, no matter what I felt about Walter, I couldn’t. I couldn't stop, but I couldn't save him. So now, do I have this idea that if I do everything in my power to save this dog, to be good to this dog, that somehow, magically, he will turn into Walter? Yeah, that was the idea.

AKT: At that moment I felt more like Greta Garbo. I hoped not.

SN: But it was that transference, that feeling of privilege that wife Number One picks up on: that that dog is not Walter? You know, like, no matter what you do, right?

AKT: In the scene on the boat in the film, he behaves like Walter, though, howling. I mean, Bing is so fantastic! When I spoke with Scott and David on Friday they told me how long they knew, and you also knew, that Bing would be Apollo. So in a way that sentence about missing the puppyhood did not apply to you. You got to experience some puppyhood with this wonderful dog!

|

| New York Film Festival 62 posters at Alice Tully Hall Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

SN: He was two when he first appeared on the scene. You know, they had just brought him, Bev, his owner. They brought him from Iowa to Connecticut. It was around early in the year 2019 and he just unloaded them in Connecticut, where Bill was ready to go to work, and maybe did start work. And then the lockdown happened, and Bing had to go all the way back home, and I kept thinking, like, you know, talk about anthropomorphism. I kept thinking this was my big thing. This was my big show, my big chance. And then I thought, I know that Great Danes don't live a long time.

And all these years were passing, because then, after that there was the strike and everything was held up for such a long time. And they kept saying, no, he's aging into his role. Because he is supposed to be six when he first comes into her life. I mean it is true that this is part of that fairy tale. Just this idea, the way he appears out of nowhere. Bing did not come into my imagination in that story until the two women in my book are actually sitting in Brooklyn and she says, I have to ask you something. And I thought, okay, what would it be? And I decided to make a dog part of the story.

But also The Tinderbox was one of my absolute favourite fairy tales ever, and it was precisely because of the size of those dogs. And so I don't think Apollo ever would have happened if I had not known this fairy tale, and had it not entered my soul so deeply as a child. Because it's a fantasy I had, you know, that not only is a dog going to appear, but it's going to be this regal, gorgeous, enormous animal.

AKT: I mean, it’s a fascinating thing with fairy tales. I just read in The New York Times Magazine about Michel Houllebecq loving Anderson!

SN: Tuesday! Yes, I saw that, too. I saw that, too. Exactly. And that particular tale. I thought that immediately. You see, wonderful! Wonderful!

AKT: I have to say, it gave me a different view of him.

SN: Me too! Me too! Me too! Me too!

|

| The New York Times critic at large AO Scott with Sigrid Nunez at the New York Film Festival Photo: Anne Katrin Titze |

AKT: Heinrich von Kleist is also quite prominent in connection to the suicide in your book. Did you ever see Jessica Hausner's Amour Fou film?

SN: No, I haven't seen it. What is that about?

AKT: It’s about Kleist, trying to find the woman who would die with him. It stars the same actors, Sandra Hüller and Christian Friedel who play Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss and his wife Hedwig in Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone Of Interest.

SN: I haven't seen it, I’m a little nervous about it, because I've heard very mixed things. You know, I'm a little squeamish about that movie. Yeah, but I hear it's quite wonderful. Should I see it?

AKT: Yes, you should. It's very powerful. I’ll send you my review later. I thought it was really really very impactful. The connection between the two movies is in the casting. The two same actors are coupled. Hüller plays not Henrietta Fogel, not the one who actually does follow up on his pact, but the first one he asks.

SN: Oh. Hmm. An interesting connection.

AKT: I have one very strange question to you. Something that stayed with me since I read your Susan Sontag book. There's a moment where she mentions the desk of Cyd Charisse. Did Susan Sontag go to the same school as Cyd Charisse?

SN: Yeah, yeah, for a while she was. Maybe it was Hollywood High, or whatever. Yeah, it was. And it was a story she told. She was in her early forties. She already had an international reputation. She knew dozens of extremely important people in all fields. And she once said, we were talking about high school or whatever, and she said that when she was in high school people would point out and say, that's where Cyd Charisse used to sit.

|

| Julianne Moore and John Turturro in The Room Next Door |

I mean Cyd Charisse was wonderful. And Susan was so, you know, like everybody else. Oh, my god! Cyd Charisse! And then, she said, “and now I take so much for granted.” Meaning because now another famous person is coming through, Mike Nichols is coming to dinner, you know this kind of thing. So I found that a very charming anecdote.

AKT: Did you see the Camp show at The Met?

SN: Yes.

AKT: Did you like it?

SN: I liked it. I liked some of it. A lot of it didn't really stay with me, really. But you know, it was fascinating.

Coming up - Sigrid Nunez on Pedro Almodóvar’s The Room Next Door, based on her novel What Are You Going Through

The Room Next Door will open in the US on Friday, December 20. The Friend in 2025.